Memory and Identity: Shoah, Israel and the Future of the Past for Soviet Jews

When people talk about the Holocaust, the countries most often mentioned are Poland, Lithuania, and Germany of course. Hungary gets a strong mention because of the speed at which the hundreds of thousands of Jews in the cities and small villages were rounded up into ghettos and deported to Birkenau, where they were swiftly processed through selections by Dr. Mengele and over 70% of each transport was sent to the gas.

Deportation 1942

Of course, each of the countries touched by the Nazi reign of terror get recalled through the recollections of their survivors, such as Primo Levi whose voice gave tribute to the persecution of the Italian Jews. And Thanks to the efforts of Father Patrick DuBois and his work in uncovering the unmarked mass graves throughout Ukraine and, now, Belorussia, the history of what transpired in those regions has come to light and is a part of the landscape of Holocaust memory.

Those who lived in the regions that remained under Soviet rule after the defeat of the Nazis continued to suffer tremendous persecutions in the Gulag and in the general living conditions under which a Jew could no longer identify publicly as a Jew. Forbidden to practice their religion, often targeted for exposure and imprisonment as traitors, memory of the suffering under the Nazis was, for many, overshadowed by the challenges they continued to face living under oppression.

Yossi Klein Halevi distributed under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

As Holocaust commemoration efforts took shape in Jewish communities around the world, the memory of the thousands killed during the war was relegated to the privacy of families and small, secret communal gatherings. Yossi Klein Halevi highlights some of the most significant aspects of this reality, while emphasizing the connection to Israel for many of the Russian Jews who later became known as “refuseniks” because of the government’s refusal to allow them to emigrate to live freely as Jews in Israel or elsewhere in the Diaspora.

“When a Zionist underground in the Soviet Union began forming memorial efforts in the Rumbuli forest near Riga, where thousands of Jews were buried in mass graves, attempts to mark the site were thwarted by the authorities. As a result, Rumbuli became a place of defiant pilgrimage. Resisting the suppression of Holocaust memory became a catalyst for rebellion against the untenable position of the Soviet Jews, denied any positive Jewish identity but forbidden, because of state and popular anti-Semitism, entirely or smoothly to assimilate. Still, the decisive influence on Soviet Jews was not the Holocaust. It was the State of Israel. ”

The isolation of Soviet Jewry from the rest of the Jewish world was pervasive, but attempts were made throughout the years to sustain a connection, provide assistance, and strengthen their ties to Israel beyond the Iron Curtain.

In 1952 an organization by the name of “Netiv” was founded by the Israeli government, whose task was to reinforce Soviet Jewry’s tenuous ties to Israel and Judaism, often at great risk.

It was Israel's breathtaking victory in the 1967 Six Day War that emboldened Soviet Jews to publicly voice their support of Israel and demand their right to make aliyah.

The wound gave way to pride: the Six Day War turned tens of thousands of Soviet men and women of Jewish origin into identifying Jews openly alienated from Soviet society and seeking to emigrate.

Like other Jews around the world, Soviet Jews experienced the whole emotional trajectory: anxiety for Israel’s survival in the weeks before the war, then relief and exultation at the astonishing victory. But for Soviet Jews, routinely subjected to taunts about Jewish cowardice (“Ivan fought at the front,” went one popular Russian saying about World War II, “while Abram hid in Tashkent”),

Rumbula forest memorial near Riga distributed under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

Israel’s military prowess meant something more: that the anti-Semites were wrong. Young Jews in Moscow greeted each other by placing a hand over one eye, simulating the eyepatch of Israel’s Defense Minister Moshe Dayan. Two days after the war, a twenty-year-old Moscow student named Yasha Kazakov wrote a letter to the Kremlin renouncing his Soviet citizenship and declaring himself a citizen of Israel in absentia. “I demand to be freed from the humiliation of being considered a citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,” he wrote.

That unprecedented letter - what sane person would draw the KGB’s attention by renouncing citizenship of a country that had no intention of letting him leave? - was smuggled abroad and excerpted in The Washington Post. Immediately afterward, Kazakov was given a visa to Israel. (Kazakov Hebraicized his name to Kedmi and went on to fight in the Yom Kippur War in a tank with Ehud Barak, and later became head of the government’s secret office dealing with Soviet Jewry.) Kazakov’s daring and his success validated two of Birnbaum’s intuitions: that a spark of Jewishness remained among young Soviet Jews, and that exposure in the West would free them.

Hundreds of letters followed - from a Kiev engineer named Boris Kochubievsky, who was ready to leave “to the homeland of my ancestors, even if it means going on foot”; from eighteen families in Soviet Georgia vowing to “wait months and years ... all our lives if necessary” for visas to Israel; from a young woman from Riga named Ruth Alexandrovich, arrested days before her wedding. You in the West are our only hope, the letter writers pleaded: the silence of the West is the Kremlin’s greatest ally. For all the refusenik heroism that was to follow, nothing quite equaled the daring of those first letter writers, defying a half-century of enforced anonymity and asserting their right to a public voice, to a name. In the Student Struggle, we memorized their letters like prayers.

The Kremlin’s response to the Jewish awakening was a hysterical anti-Semitic campaign thinly disguised as anti-Zionism. Factory workers were summoned to lectures about the unique evils of Jewish nationalism; newspaper cartoons depicted Israeli soldiers with grotesque noses and swastika armbands. Zionists were accused of the most monstrous crimes, from deliberately murdering Palestinian babies to collaborating with the Nazis. Nothing less than world peace was threatened by Zionist aggression. The problem with “Abram,” it turned out, was not that he didn’t know how to fight, but that he fought all too well. The notion of Zionism as racism was born in the Soviet Union; and so, too, was the ease with which anti-Zionism may mutate into anti-Semitism.

Lessons of Struggle for Soviet Jewry Remain Relevant

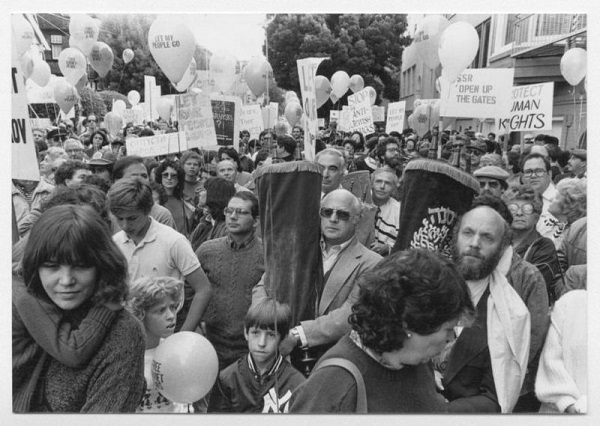

The refuseniks took open action to protest the ban under the battle cry, “Let My People Go!”, acts that were particularly courageous in light of the grave consequences their predecessors had suffered after the 1948 founding of the State of Israel, when Zionists in the USSR who openly expressed their bond with Israel, were arrested, many fired from their jobs, some sentenced to long terms in prison, others deported and exiled to Siberia.

Their brave demonstrations accelerated and their demands extended to include unrestricted emigration to the United States and West Germany, as well as freedom of religious expression within the Soviet Union itself. “The fact that a million Jews were striving to immigrate to Israel, but were trapped behind the Iron Curtain by the Soviet authorities, penetrated the world’s consciousness,” underscores Yuli Edelshtein, the former refusenik who became Deputy Director of the Knesset.

Other Jewish activists worked clandestinely to organize ulpanim for learning Hebrew; underground seminars on Jewish topics; kindergartens; activities by teenagers; events and festivals; underground religious activity celebrating the Jewish festivals (e.g., Purimshpils); publications, including samizdat (clandestine) publications; underground Jewish art. These secret meetings took place in people’s homes, putting individuals and their families at risk of arrest and harassment, were their hideouts to be uncovered by Soviet authorities and informants.

Soviet Jewry rally on Simchat Torah

Between 1967 and 1989 Jewish activism in the USSR and the international support it received from the U.S., Israel and world Jewry shaped a generation of Jewish human rights advocates across the globe, and gave the Jewish people one of its most remarkable, modern-day success stories. The global campaign had a tremendous impact, imbuing a shared sense of Jewish peoplehood among Jews the world over.

Having learned the lessons of the Holocaust, Jewish communities were determined to assert themselves in defense of their brothers and sisters locked inside the USSR. Arming their protests with slogans such as “Never Again!”, Jews of all ages and backgrounds – from community leaders, artists and intellectuals, to students and housewives – protested outside Soviet embassies and consulates year in and year out until the power of their demonstrations were backed up by their governments’ exertion of diplomatic pressure on the Soviet Union.

Indeed, the Soviet Jewry movement caught the attention of statesmen and public figures throughout the West, who considered the USSR’s Jewish policy to be in violation of basic human and civil rights, such as freedom of immigration, freedom of religion, and the freedom to study one’s own language, culture and heritage. The redemption of Soviet Jewry became an impetus for the awakening of oppressed peoples everywhere, and continue to inspire the pursuit of freedom from persecution for both Jews and non-Jews.

In the end, the struggle succeeded, the floodgates opened, and Jews gained the right to immigrate – one million to Israel and around half a million to other countries. Their activities resulted in a slow trickle of immigration between 1969-1973, and some 150,000 Jews succeeding in making aliyah. The massive influx only arrived with the fall of the Soviet regime in 1990.

The redemption of Soviet Jewry would eventually be an impetus for the awakening of oppressed peoples everywhere. The endurance and efficacy of Russian Jewish activism fueled the broader anti-communist movements found in all the Soviet republics and satellite countries, thereby significantly contributing to the fall of the Iron Curtain, begun in 1989 in the Eastern Bloc and climaxing with the 1991 collapse of the USSR.

Dr. Elana Yael Heideman, Executive Director of The Israel Forever Foundation, is a dynamic and passionate educator who works creatively and collaboratively in developing content and programming to deepen and activate the personal connection to Israel for Diaspora Jews. Elana’s extensive experience in public speaking, educational consulting and analytic research and writing has served to advance her vision of Israel-inspired Jewish identity that incorporates the relevance of the Holocaust, Antisemitism and Zionism to contemporary issues faced throughout the Jewish world in a continuous effort to facilitate dialogue and build bridges between the past, present and future.

Recommended for you:

ISRAEL RETURNS: SOVIET JEWS RETURN TO ZION

What can you learn about your Jewish identity from the journey of Soviet Jews back to Zion?

About the Author