The Fate of Our Generation

By Dr. Daniel Gordis

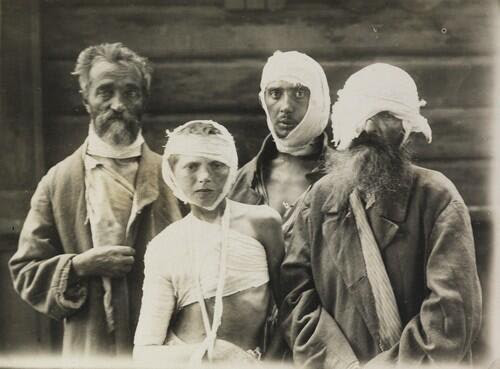

Survivors of the pogrom in Khodorkov, 1919 (courtesy of National Library of Israel)

IDF security forces searching for terrorist responsible for attack in Tel Aviv, April 7, 2022 (photo courtesy of Hananya Naftali)

On April 29, 1956, twenty-one-year-old Roi Rotberg was patrolling the fields of Nachal Oz, just outside Gaza, where he lived, on horseback. Accustomed to seeing Gazans illegally picking the kibbutz’s fields, when Rotberg saw a group of Arabs in the fields, he rode toward them to get them to leave. But it was a trap, and as Rotberg approached the “farmers,” a group of fedayeen suddenly appeared, shot and killed Rotberg, then dragged his body into Gaza, where it was horrifically mutilated.

Coincidentally, Moshe Dayan, who was then Chief of Staff of the IDF, had met Rotberg a few days earlier. He attended the funeral and delivered a brief eulogy (merely 238 words in total) that became Dayan’s—and then, many Israelis’—classic statement about the inevitability of a long and costly conflict between Israel and its neighbors. While Dayan’s message and that of Abraham Lincoln in Gettysburg were entirely different, Dayan’s eulogy, also given at the “battlefield,” has become as iconic in Israeli life as has Lincoln’s in the culture of America.

I had planned to write about the Rotberg eulogy today, because next week (when because of Passover we won’t be posting a column) is the anniversary of those events. Horrifically, though, the terror attack in Tel Aviv last week reminds us how timely Dayan’s immortal words are, even today.

Here is a recording of Dayan reading the eulogy (the photo is of him at the funeral, reading the text), followed by the finest English translation I have found.

Yesterday with daybreak, Roi was murdered. The quiet of a spring morning blinded him, and he did not see the stalkers of his soul on the furrow. Let us not hurl blame at the murderers. Why should we complain of their hatred for us? Eight years have they sat in the refugee camps of Gaza, and seen, with their own eyes, how we have made a homeland of the soil and the villages where they and their forebears once dwelt.

Not from the Arabs of Gaza must we demand the blood of Roi, but from ourselves. How our eyes are closed to the reality of our fate, unwilling to see the destiny of our generation in its full cruelty. Have we forgotten that this small band of youths, settled in Nahal Oz, carries on its shoulders the heavy gates of Gaza, beyond which hundreds of thousands of eyes and arms huddle together and pray for the onset of our weakness so that they may tear us to pieces — has this been forgotten? For we know that if the hope of our destruction is to perish, we must be, morning and evening, armed and ready.

A generation of settlement are we, and without the steel helmet and the maw of the cannon we shall not plant a tree, nor build a house. Our children shall not have lives to live if we do not dig shelters; and without the barbed wire fence and the machine gun, we shall not pave a path nor drill for water. The millions of Jews, annihilated without a land, peer out at us from the ashes of Israeli history and command us to settle and rebuild a land for our people. But beyond the furrow that marks the border, lies a surging sea of hatred and vengeance, yearning for the day that the tranquility blunts our alertness, for the day that we heed the ambassadors of conspiring hypocrisy, who call for us to lay down our arms.

It is to us that the blood of Roi calls from his shredded body. Although we have vowed a thousand vows that our blood will never again be shed in vain — yesterday we were once again seduced, brought to listen, to believe. Our reckoning with ourselves, we shall make today. We mustn’t flinch from the hatred that accompanies and fills the lives of hundreds of thousands of Arabs, who live around us and are waiting for the moment when their hands may claim our blood. We mustn’t avert our eyes, lest our hands be weakened. That is the decree of our generation. That is the choice of our lives — to be willing and armed, strong and unyielding, lest the sword be knocked from our fists, and our lives severed.

Roi Rotberg, the thin blond lad who left Tel Aviv in order to build his home alongside the gates of Gaza, to serve as our wall. Roi — the light in his heart blinded his eyes and he saw not the flash of the blade. The longing for peace deafened his ears and he heard not the sound of the coiled murderers. The gates of Gaza were too heavy for his shoulders, and they crushed him.

There is much to say about the eulogy, which we cannot cover here. The “heavy gates” are a reference to Samson. The word for “blade” is the same (unusual) word used in the Binding of Isaac story. The sense of obligation to Jews who were not saved, because there had been no Jewish state, is central. And the looming 1956 Suez War, just months away, may well have influenced Dayan’s message. All that, and much more, for another time.

For now, though, one other biblical reference.

Thousands of years before Moshe Dayan, the commander of the biblical King Saul’s forces, Abner, asked Yoav, the captain of David’s men, “Must the sword devour forever?” Yoav offered no answer in the biblical text, but millennia later, Dayan, the latest commander in the Jews’ long history, answered unequivocally. “Yes.”

Yes, the sword will consume forever.

And that is why the photos at the top of this page matter. Tel Aviv on Thursday night was a horror in too many ways to enumerate here. But if there is any consolation, it is to be found in comparing the scene after a pogrom in Khodorkov and the scene after the attack in Tel Aviv as security forces hunted down (and ultimately shot and killed) the murderer.

Before the Jews had a state, we were the first photograph. We could be slaughtered, with no repercussions for anyone. As we learned again this terrible week, we’re not impregnable now, either. But this time, there is a cost to the murder of Jews.

On Israel’s 50th anniversary, almost a quarter of a century ago, Ariel Sharon wrote a column in which he summarized Moshe Dayan’s worldview, with which we conclude this column:

"We cannot secure every water pipe from vandalism, or prevent the uprooting of every tree. We do not have the capacity to prevent the murder of workers toiling in vineyard, or families when they are asleep.

But we do have the power to exact a very high price for our blood."

Despite the anger, the fear and the grief, that makes all the difference.

Recommended for you:

About the Author