The Universalization and Contemporary Abuse of Holocaust History

The lessons of the Holocaust have become public property, with an emphasis on universalization that often results in the erasing of the unique experience of Jews. Awareness about the Holocaust has begun to fade, diminished under the passage of time as well as the weight of Holocaust distortions, inappropriate comparisons, Holocaust “fatigue,” and, most recently, the return of traditional anti-Jewish tropes that disregard the significance of the Holocaust. Dr. Elana Heideman, Executive Director of The Israel Forever Foundation, explores the misappropriation of Holocaust history and imagery and discusses what we can do to change the current trends.

Contact us for more resources for Holocaust and Israel education, or custom programs suitable for families, educators, and communities.

Support our efforts to provide resources like this one among other methods of preserving Holocaust memory.

Listen to the podcast on Spotify now

DOWNLOAD THE RESOURCE FOR EASY USE

What was once a sacred and respected realm of human suffering and atrocity, shrouded in the immense pain and brutality of its truth, has now become fodder for common conversations and comparisons in classrooms.

With the growing disappearance of survivors we have received as well the fading of the mystification that had once protected the integrity of the Holocaust as a historical event with lessons for all of mankind.

Unfortunately, those lessons have since been distorted, blurred, manipulated for the purpose of political gain, social justice, and an overly generalized understanding of what the Holocaust was and what it means for humanity today.

These are issues of serious concern for anyone interested in the future of Holocaust memory and the protection of its historical truths. The future role of the Holocaust in public and private discource will be determined by this cycle of transformation.

Not the events, their context, nor the experiences of the primary victims of the Holocaust matter any longer. There are newer, more modern atrocities to shock and revile us, and there is nothing so sacred about the murder of some unverifiable number of Jews that protects it from widespread misrepresentation and misuse.

There is no one organization, body, or group that owns the Holocaust, or that can protect it from the infiltration of these forces, and only a concerted effort to negate the trends will have any impact on the future. Sadly, the lack of coordination or cooperation has fostered an imbalance in what are considered accepted truths about the Holocaust. When the Jewish world is so fragmented, shattered by the wide spectrum of differences in what we each believe about Jewish identity, history or Jewish values the Holocaust is a shared element of reference that is applied whenever it feels fitting.

The differences of opinion and widespread feeling of ownership or belonging to the Holocaust have perhaps weakened our ability to contend with the realities that now present themselves on every platform, in every scenario - the Holocaust as a joke, as a mere moment in history that is no longer relevant unless it is through exaggerated comparisons. Everything is open to debate and subjective analysis, every element of the Holocaust in particular diminished to a simplicity that outright defies the horrific reality that it was.

Open-ended comparisons in the classrooms and on campuses have led to generalizations about the Holocaust from which historical memory may never recover. There are no limits to how much we can impose boundaries on forms of presentation and representation when it comes to teaching and learning about the Holocaust, just as much as we cannot control the growing genre of fictional films and literature that negate factual truths entirely, or worse, justify the behavior of the murderers and ignore the innocence of their victims - even to the extent of humanizing the Nazi and a simultaneous revival of the dehumanization of the Jew.

Comparisons that bear no resemblance to the events as they were lived trivialize the experience and diminish the value of the true lessons that the Holocaust can teach. Instead, contemporary applications of language once specific to describing the Holocaust are being used to describe events and purposes that are unrelated to it. More often than not, the information strips the Jews of any unique experience of persecution, hate, suffering; of any special right to the history, the memory or its lessons; and certainly any understanding that should be granted to the Jewish nation.

QUESTIONS FOR CONSIDERATION:

- How can we identify what are valid and invalid sources for Holocaust information and education? How can we ensure that the truth is preserved and presented against the rapid spread of misuse and misinformation?

- “We are stripping the truth and replacing it with fiction.” What are some major issues that can arise from presenting “lighter” or “alternative” education on the Holocaust or other subjects?

- What obligations do we have, as educators, parents, or even students, to consuming and conveying information about the Holocaust?

Unfortunately, amidst the cancel culture generation we are living in, Jewish significance to the Holocaust is quickly being cancelled right alongside the denial of Jewish connection to Jerusalem, The Temple Mount, the Land of Israel. Even to say that the Holocaust, like Israel, are an integral part of Jewish identity is no longer entirely accurate. While educators and museums, parents and grandparents even, strive to teach the many faceted elements of the events that transpired, voices of second and third generation descendants of survivors of the Holocaust increasingly are channeling their personal family experiences to advance their contemporary desires and causes of interest.

Much like politicians and activists from every side, ghettos, Nazis, concentration camps, and Auschwitz are now the easiest point of comparison by which one can direct their accusations and outrage. The trends to use yellow stars of David and calls of CovidCaust casting the handling of the global pandemic as the modern day Holocaust, with quarantine “just like” the experiences of Anne Frank in hiding from the Nazis, and similar calls casting the crisis in Gaza in the same light, are promoted from among the very groups that we would hope know the boundaries to which we should be obliged, out of respect of the dead, and out of respect for historical truth.

Using their “privilege” as Jews and as descendants of survivors, they have become the leaders of movements ranging from Activists against the Silent Holocaust of Vaccine Mandates, to IfNotNow calling for the destruction of Israel - essentially calling for another Holocaust of Jews, just under the now-palatable mantra of anti-Zionism and anti-Israelism.

This issue of Jewish “Holocaust privilege” is increasingly rationalized through open dialogue on social media in particular, as well as among colleagues and peers in the workplace. It is arousing a scary new version of hatred and resentment against Jews.

For example, in a group coping with PTSD, one young woman in her 20’s made the claim that she had complex PTSD due to generational trauma because her great-grandparents were in concentration camps during the Holocaust. A fellow member proclaimed “I know I shouldn’t care but it feels like a means for this otherwise privileged woman to claim sympathy for a trauma that is not her own.”

The conversation continued as another member declared, "How is it possible this woman can blame her problems on the supposed experiences of her parents in the Holocaust? It’s all just made up.” Another rants against her as a “grammar nazi”, that she must have learned well from her parents. And another - “How anyone can be taken seriously saying something triggered her PTSD that she claimed was from generational trauma caused only by the Holocaust? Only Jews believe they have such rights.”

Invariably the discussion deteriorates to otherwise antisemitic expressions, more often than not including both traditional and modern expressions of hate. Jewish members of these groups are silenced into submission and the hate spreads like wildfire. And at its core, an abuse of the Jew because of the use of the Holocaust in self-expression.

The result is the erasing of the Jew, and the Jewish right to emotion, sympathy, or Jewish memory. Whether it is the Jews as privileged, white, thieving, powerhungry perverts of society or the murderous demonic genocidal Jew-state, we are seeing trends similar to the negative depictions and fabricated accusations against Jews that created the environment for the Holocaust to occur in the first place. And it isn’t one leader, one politician or group, one faction of society. It is everywhere. And more and more, it is the Jews who are silenced.

Each and every situation leaves a wake of confusion for some, shame for others, fear or disgust, and, too often, an increased hate of anything that has anything to do with Jews - whether it be the Holocaust, Israel, or any public Jewish expression. A whole generation of Jews is confronting head-on the tension between Jewish universalist principles and the idea of Jewish particularity — that Jews possess special obligations toward one another, that we had any unique experience of suffering during the Holocaust, or that we have the right to defend ourselves for the particularities that have allowed the Jewish nation to outlast every tyrant and to continue to survive and thrive for 3000 years.

Perhaps this is the Jewish power that echoes the Nazi propaganda, promoting fear of the Jew, the eternal threat? With Jewish sovereignty again a reality, the texts written during the history of our victimization become speculation, and accusations of the Jew/Israel as the evil of the world are, once again, given free reign.

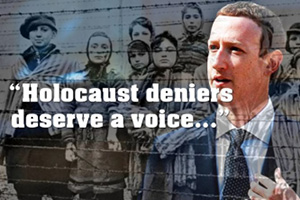

A secondary effect of the universalization of the Holocaust is the affirmation of Holocaust revisionist conspiracy theories that thrive among the general population. For example, asked if the Holocaust was a hoax, Amazon’s Alexa replies, “some claim the Holocaust is a hoax – or an exaggeration – arising from a deliberate Jewish conspiracy designed to advance the interest of Jews at the expense of other people.” It has also been reported that Alexa’s responses include “Jews control the world’s financial systems and media” and that “Israel is guilty” of “ethnic cleansing on a massive scale and serial human rights abuse, including war crimes.”

Is it reasonable that this information should be so automated that essentially any individual can be exposed to the idea that the Jew harbors evil intent toward mankind? What is the proper course of action? The spread of the lies is so massive, the real question is whether or not it could ever be contained. The use of the Holocaust has found a place in every platform - from social media to personal encounters, in education and politics, where Jews are accused of exploiting the Holocaust as an excuse for alleged Israeli aggression and Jewish racism.

QUESTIONS FOR CONSIDERATION:

- What are the crucial elements for Holocaust education? What aspects need to be discussed?

- How can you discuss the Holocaust within the current limits of attention and tolerance?

- What are some creative ways of avoiding the pushback on the "heavy" or "touchy" subject of the Holocaust?

- Is teaching the Holocaust “in context” necessary? What does that mean?

We all know that the campuses have become the hotbed of thriving antisemitism, and the whole of academia is compliant, sadly, in allowing the libels to spread. For example, one master’s thesis claims that Holocaust education serves to “obscure Jewish privilege, deny Jewish racism and promote the interests of the Israeli nation-state,” and charges that “claims of Jewish victimhood are no longer based in a reality of oppression, but continue to be propagated because a victimized Jewish identity” is “beneficial to the organized Jewish community and the Israeli nation-state.”

Jews are so often accused of co-opting antisemitism to fend off criticism of Israel that contemporary anti-Semitism is deemed by some to be largely a myth, or it is excusable. “How do Israel and the Jews love using antisemitism for their own purposes? Let me count the ways.” Under the guise of searching for ways to improve the world, to fight for the social justice of every group (other than our own Jewish people sadly), the Holocaust is coopted through a universal slant.

Another popular voice proclaims that open comparison is the only way to uncover the truth behind the Jewish agenda. They ask, “Is it an irresponsible overstatement to associate the treatment of Palestinians in Gaza with the Jewish criminalized Nazi record of collective atrocity?” The suggestion that any pattern of conduct on behalf of Jews in Israel, their soldiers or their government as a “holocaust-in-the-making” represents a rather desperate appeal to public opinion to claim genocidal tendencies when every shred of fact proves otherwise.

The lie is easier to believe, and when promoted by Jews themselves, especially by a survivor or their descendants, then certainly it must be true. When extreme leftist professors claim that “Israel uses Holocaust education to prepare its youngsters for the task of brutalizing the Palestinians,” it carries more weight than any factual truth no matter how many leaders, generals, soldiers, and, yes, even Arabs in Israel, Judea, Samaria and even Gaza themselves deny the outrageous lies. It is emotive, it arouses sympathy for the victim and hatred for the oppressor. And the “use” of the Holocaust through the universal ubercomparative lens is to blame.

A Jewish news anchor targeted a fellow reporter for likening Dr. Fauci’s attempts to curb the spread of the Covid pandemic to Nazi doctor Josef Mengele, the doctor of Auschwitz who infamously performed a series of medical experiments on twins, many of whom were children, and whose white-gloved hands directed millions to their death. The illegitimate comparison is one of many that have become popular in social dialogue, and one we have seen time and time again. From Ocasio-Cortez, Bill Clinton to the Pope, Serbian holding pens for Muslim Bosnians were described using the same term for China and Gaza.

Anti-abortion activists routinely refer to abortions as a “Holocaust of the unborn” and gun rights activists have used the Holocaust as an excuse to advocate liberalizing gun laws even further. Former President Trump compared American intelligence agencies to those of the Third Reich, while the left accused Trump of being the new Hitler. Left-wing figures invoked Nazism in reference to George W. Bush while Natalie Portman compared meat-eating humans to Nazis. And of course, countless BDS-niks and other anti-Zionists have been saying or implying for many decades the hideous slander that Israel is a Nazi state. Unfathomable as this may sound to some people, Trump was not Hitler, and Fauci was not Mengele. There are legitimate ways to draw connections, but using the labels callously will only damage the integrity of the memory and lessons we need to protect for the future.

“By highlighting the Holocaust as the ultimate example of man’s capacity for evil, it became the yardstick by which all evil was to be measured. Now, whenever someone wants to identify a person or an idea as “evil,” the Holocaust provides the grounds for comparison in spite of no commonalities between the contexts.” Jews respond with outrage at the times they feel it is inappropriate, but the echoes of silence are deafening. No Jewish resistance to the comparative trends may ever matter in the grand scope of the future. In fact, we have, perhaps, created the challenge for ourselves.

“Holocaust trivialization” is now in our schools. In the very places that are now mandated to have a Holocaust curriculum. Yet any teacher can teach it, no training, no background understanding, no standard of truth required. Everything remains open to interpretation. “Perhaps the Jews had it coming to them?” Transformative in our understanding of humankind’s darkest impulses, we believed that the Holocaust could teach the next generation that one can learn hard truths, inherit pain and memory, and also be responsible for protecting the dignity of its victims honestly.

Indeed, many schools around the world now include Holocaust education in their curriculum, but how the subject is taught is creating new problems. Teachers who should be trained to present difficult material in ways that do not overly traumatize youngsters, while at the same time offering them ways of using this hard learning to make a difference in the world, are ill-equipped, or perhaps indifferent, to how their lessons are being translated into real life. Because alongside learning about the Holocaust and the Nazis, in Melbourne, a little 5 year old boy was subjected to such horrific bullying and intimidation by classmates calling him “Jewish vermin”, “the dirty Jew” and a “Jewish cockroach.”

A 12 year old boy surrounded by about 9 other kids who threatened beatings if he did not kiss the feet of a Muslim boy. In Indiana, a girl’s locker was etched with “Why didn’t you go to the gas with the rest of the Jew Swine?” In France, England, Canada, New York, LA, you name it - it is happening, and what we once believed would stop Jewhatred has now become its primary slur - the Jews, to blame for the ills of the world, the hindrance to peace among men, the stranger among us, the eternal other, succeeded in making the Holocaust and Auschwitz the rallying cry for yet another elimination of Jews from the world.

These are the realities paving the way for more recent demands that “the other side” of the Holocaust story be represented alongside the sharing of Holocaust history - no longer just the stories of the non-Jewish victims, but now of the perpetrators themselves, and any modern manifestation one thinks fits that mold. Hence the essay questions in high schools, “Please explain why Hitler believed he was right.” Holocaust lessons usually constitute a few mere hours, very generalized, and nearly always sanitized of the pain, the horror, and the relevance of the unique treatment of Jews as a bulwark for human understanding of repeated patterns.

Elie Wiesel once said about the Holocaust, “One should take off one’s shoes when entering its domain; one should tremble each time one pronounces the word.” Ever faithful to his Jewish origins and values, his concern about their universality possessed limits, a lesson we should all take into serious consideration. It was years later that he proclaimed, "I cannot use the word 'Holocaust' anymore. First, because there are no words, and also because it has become so trivialized that I cannot use it anymore. Whatever mishap occurs now, they call it 'holocaust.' A commentator describing the defeat of a sports team, somewhere, called it a 'holocaust.' A description of the murder of six people, and the author called it a holocaust. So, I have no words anymore."

It is in his absence that we, the next generation of protectors of memory and truth, we must find the words. Only by addressing the value of the particularity of the Jewish experience and history of the Holocaust can we offer a way forward, psychologically as well as logistically, for the next generation. We must teach others how to protect the integrity of the history by avoiding distortions or illegitimate parallels while still applying the many lessons that one can learn about human behavior, decision making, leadership and responsibility towards one’s fellow man - all without minimizing the truth of that dark realm which defies our imagination and our nightmares.

Most people do not want to think about genocides. They do not want to think about the Holocaust or other mass killings. They are very uncomfortable with the fact that these events happened, and most cannot state any facts about the atrocities themselves. Without a real effort to retain their memory, the Holocaust, the voice of survivors and the meaning for humanity may simply disappear from history. And if we are not careful, and if we do not act in our communities and our schools, in our homes and houses of prayer, we will see a continued deterioration of the use and abuse of Holocaust until it no longer resembles any truth at all.

And this is a task for all of us.

QUESTIONS FOR CONSIDERATION:

- How is desensitization to violence through social media and pop culture affecting how we relate to the Holocaust?

- What makes the Holocaust different from other atrocities? How can we preserve those differences?

- Does recognizing the Holocaust as different affect the acknowledgement of other tragedies? Does trying to draw parallels to the Holocaust actually help the memory of it or any other tragedy?

- Does “being Jewish” help or hurt the discussion and connection to the Holocaust, and how?

- How does applying related language - “Holocaust”, “Nazi”, “concentration camp”, “genocide”, etc. - to modern situations or humor affect Holocaust memory? Should it be permitted? Under what circumstances?

- What steps can individuals take to counter bias and promote facts, especially when it comes to Holocaust education and memory?

DOWNLOAD THE RESOURCE FOR EASY USE

Support our efforts to provide resources like this one among other methods of preserving Holocaust memory.

Recommended for you:

Explore our other resources to preserve Holocaust memory

Remember, reflect, and together we will carry the past into the future

About the Author