The Zionist Dream in the Poconos

By Morris Dickstein

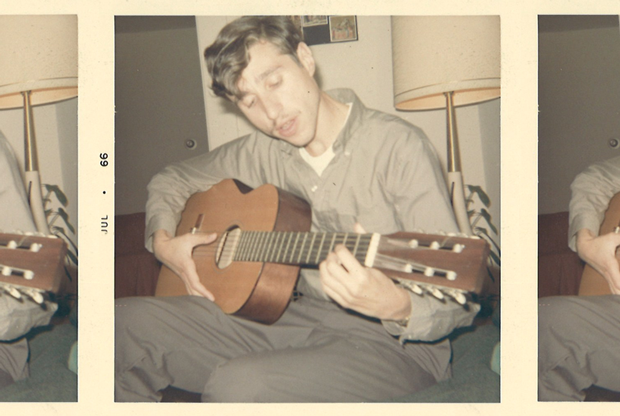

Morris Dickstein - New Haven, 1966. (Photo courtesy Liveright Publishing)

An excerpt from the new memoir ‘Why Not Say What Happened’ conjures lost summer worlds.

I arrived at Massad the same year, 1958, that Leon Uris’s Exodus dominated the bestseller list, soon to be followed by an even more popular film version starring Paul Newman as the Sabra hero. They enshrined a tale that left American Jews bursting with unearned pride, easing the pain and unspoken guilt over what had befallen the Jews in Europe. It told how the Zionists had wrested a homeland from the ashes of the Holocaust and how a new kind of Jew, bold, strong, determined, had sprung forth to supplant the persecuted Jew of the Diaspora—the meek, unworldly Talmud scholar, the exploited worker, the small urban storekeeper like my father. This might explain why Zionism had scarcely impinged on my Orthodox Jewish childhood.

I had carried around the blue-and-white collection box of the Jewish National Fund, raising money to plant trees in Israel, green forests in an arid land. But many religious Jews, though excited by the David-and-Goliath story of the birth of the Jewish state, saw Israel as a dubious experiment at odds with the fundamentals of the faith.

The epitome of Zionism was the kibbutz, which meant tractors, socialism, and free love, with children separated from their parents and brought up in common as sun-baked young pagans. There were religious Zionists too, pioneers in khaki shorts with tiny knitted skullcaps, but Zionism scorned what it saw as the passivity and otherworldliness of ghetto Judaism, as it also spurned the assimilation and material values of America’s Jews. For many kibbutzniks the Soviet Union was the preferred model; for others it was European social democracy. Giving up the dogmas of religion, they grew fanatically devoted to political disputation and ideological commitment, a fractured legacy of the European Left.

The pervasive Zionist atmosphere in Camp Massad embraced more than the spoken language. Each bunk was named after a town or kibbutz in Israel, usually a place we knew nothing about apart from its exotic name.

My first bunk was called Beit Alfa, but this meant little to me. When I visited it a few years later, I saw the most exciting archaeological site in Israel. Its masterpiece was the tiled floor, with strange biblical and zodiac design, of a synagogue some fifteen centuries old. While evenings in the Catskills had been filled with the fading remnants of vaudeville comedy and Yiddish theater, Massad evenings revolved around Israeli dances and songs, such as the lilting tune about a lass called Simona from Dimona. Hey Simona, mi’Dimo-ona, hey Simona-mona, mi’Dimona. One counselor joked that, hey, Dimona was no more than a gas station in the Negev; that was good for a laugh. Who could imagine that it was the future site of Israel’s nuclear program, and later a magnet for Russian immigration?

Even then we didn’t quite grasp that this was a song about a Sephardi girl—a shkhora, or dark-skinned girl—at a time when these so-called oriental Jews were still an exotic but growing underclass in Israel.

After a two-thousand-year hiatus, Israel seemed an astonishing political creation, an almost miraculous fulfillment of a millennial dream. I don’t recall that the Arabs of Palestine were ever mentioned, though the enmity of the surrounding Arab states was a constant theme, an echo of the vulnerability Jews had felt through centuries of pogroms. As I read Moshe Dayan’s vivid diary of the 1956 Sinai campaign, I felt at once proud of Israel and anxious about its fate. But in my real life it remained a remote fantasy, though the dances, the songs, the tales of the kibbutz, and the strange yet familiar names of the towns seemed magically appealing; they projected their own vigorous reality. The Zionist project, Ahavat Tzion (the love of Zion), the attachment to the biblical land, was reshaping us into different kinds of Jews, and my best camp friends would eventually emigrate, something I was never tempted to do, though I wondered at moments what such a life might be like for me. Zionism made us imaginary inhabitants of a place most of us had never seen.

Read the rest or the article at TabletMag.