A Yom Kippur Melody

Spun from grief, atonement and memory

By Matti Friedman, Times Of Israel

For many Israelis, the ancient observance of Yom Kippur is inextricably linked to a modern trauma — the anniversary of the outbreak of the 1973 war, which took Israel by surprise, shattered its confidence and left more than 2,500 soldiers dead in three weeks of desperate fighting.

When Yom Kippur is marked across Israel and the Jewish world, many synagogues will sing one of the service’s central prayers to a tune written on a kibbutz in northern Israel 22 years ago. The story of how that tune came to be is an illustration of the unique mix of traditional practice and national remembrance that has come to infuse Israel’s observance of the most solemn day of the Jewish calendar.

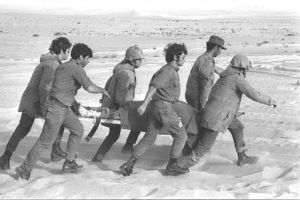

Israeli artillery on the Golan Heights, 1973

Copyright © CC BY-SA Israel Defense Forces

“Unetaneh Tokef,” one of the key prayers of the Days of Awe, describes God’s judgment and the insignificance of human beings who are, the prayer says, “like a broken shard, like dry grass, a withered flower, like a passing shadow and a vanishing cloud, like a breeze that blows away and dust that scatters, like a dream that flits away.”

The magnitude of the casualty numbers became clear to Israelis after the war ended on October 25. And no community in the country had suffered more losses per capita than Beit Hashita.

Copyright © Military Photos

“When the war was over, a few days later rumors started flying around the unit,” kibbutz member Amihai Yarchi told a crew from Channel 1 TV two years after the war. The first rumors said Beit Hashita had lost 10 members, then 11. “Of course I refused to believe it,” he said.

One day after the war’s end, 11 small army trucks pulled through the kibbutz gates, headlights on even though it was daytime. Each bore one coffin. The dead men were the kibbutz’s next generation — young workers and fathers, most of them reservists. For a small and tightly knit community, it was a nearly incomprehensible loss.

“I have two Yom Kippurs,” Yarchi recalled in a 1991 TV documentary. “One Yom Kippur is the day the war broke out, and the other Yom Kippur belongs to the rest of the people of Israel and is passed from generation to generation. The Yom Kippur of the war was the end of an era and the beginning of a new era, one that I think Beit Hashita and the state of Israel have not yet recovered from.”

“It was something terrible,” kibbutz member Rachel Meroz recalled in the same documentary, describing the 11 simultaneous burials, “like the destruction of the third temple.” From 1973 on, Yom Kippur on the kibbutz became a day of mourning for the men killed in the war.

The next year, 1974, a member of Beit Hashita, Dorit Zameret, wrote “The Wheat Grows Again,” an expression of longing for the kibbutz’s lost sons and of surprise that the agricultural cycle continued as if nothing had changed. It remains one of the most touching examples of the Israeli genre known as “memorial songs,” which typically weave mourning for fallen soldiers with imagery of the beauty of the country they died defending.

The grief of Beit Hashita was still raw 17 years later, in 1990, when one of Israel’s best-known songwriters, Yair Rosenblum, came to stay at the kibbutz.

Rosenblum was famous for writing dozens of hits, including the most popular numbers sung by the military entertainment troupes that topped the Israeli charts in the 1960s and 1970s, like “Song for Peace” and “Ammunition Hill.” As Yom Kippur approached, he “decided to give something personal, something of himself, to this special day,” kibbutz member Michal Shalev wrote. Her recollections were published by the kibbutz in a booklet about Yom Kippur in 1998, two years after Rosenblum died of cancer.

“At first he thought he would write new music for ‘Kol Nidrei’,” she wrote, referring to the prayer that opens the service on the eve of Yom Kippur, “but at the same time he looked for other ideas.” Flipping through a High Holidays prayerbook, he came across “Unetaneh Tokef.” The prayer’s name, roughly translated as “Let us relate the power,” is taken from its opening phrase: “Let us relate the power of this day’s holiness.” In 1974, the prayer had served as the inspiration for Leonard Cohen’s 1974 song “Who By Fire.”

Thought to be considerably more than a millennium old — its precise roots have been lost to history — the text of the prayer could not have been farther from the kibbutz’s militantly secular approach to Yom Kippur, which members had marked as a day of meditation and honoring the dead that had nothing to do with a God whose nonexistence they considered to be an article of faith.

The prayer, in contrast, depicts humans as negligible in comparison to a deity described as an all-powerful shepherd, a righteous judge, and an eternal power over the lives of men.

On Rosh HaShanah it is inscribed,

And on Yom Kippur it is sealed:

How many shall pass away and how many shall be born,

Who shall live and who shall die,

Who shall reach the end of his days and who shall not,

Who shall perish by water and who by fire,

Who by sword and who by wild beast,

Who by famine and who by thirst…

“Yair read it and knew this was what he was looking for,” wrote Shalev. “He didn’t shut his eyes all night, and waited for the morning, for the house to be empty of people and for a chance to play uninterrupted.” When Shalev arrived at about 10 a.m., she found Rosenblum “writing and crying.” He played her a tune he had written for the prayer — a melding of European cantorial melodies, Sephardic tunes and modern Israeli music. “It was one of those moments in which you feel shaken and an excitement that has no room for words,” she wrote.

Hanoch Albalak, a kibbutz member known for his singing voice, was chosen to perform the prayer at the kibbutz’s Yom Kippur service. “Eleven members fell in that war, and nearly all members of the kibbutz have some kind of connection to that — fathers, sons,” Albalak, now 77, recalled this week. “The atmosphere during the ceremony is that of a dark cloud hovering over the kibbutz.”

Yom Kippur War Memorial Service

Copyright © Tsafrir Abayov/Flash90

The song was sung at the end of the ceremony on the eve of Yom Kippur that year, 1990. Rosenblum had introduced an unapologetically religious text into a stronghold of secularism and touched the rawest nerve of the community, that of the Yom Kippur war. The result appears to have been overpowering.

“When Hanoch began to sing and broke open the gates of heaven, the audience was struck dumb,” Shalev wrote.

“Something special happened,” another member, Ruti Peled, wrote in the same kibbutz publication from 1998. “It was like a shared religious experience that linked the experience of loss (which was especially present since the war), the words of the Jewish prayer (expressing man’s nothingness compared to God’s greatness, death to sanctify God’s name and accepting judgment) and the melody (which included elements of prayer).”

“When I sang, I saw more than a few people crying,” Albalak recalled. Word spread after the holiday, and a year later, in 1991, Channel 1 TV filmed a documentary about the prayer and the kibbutz’s fraught relationship with Yom Kippur. Rosenblum’s tune began to catch on. In Israel, it is now one of the most widespread melodies used for the prayer that marks the height of the Yom Kippur service.

The tune owes its power to the way it fits the haunting words of the prayer, but also to the fact that its origins link the two most powerful strands in the modern Israeli experience of Yom Kippur — the weight of Jewish tradition and the weight of the tragedies of 1973.

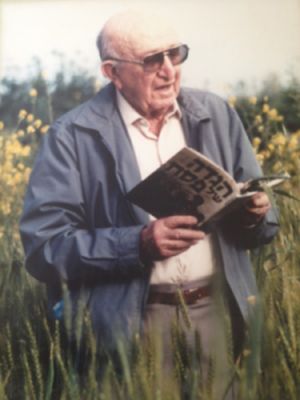

Aryeh Ben-Gurion

Copyright © Kibbutz Institute for Holidays and Jewish Culture

The late Aryeh Ben-Gurion, the nephew of Israel’s first prime minister and a member of Beit Hashita who was an authority on the kibbutz movement’s Jewish observance, noted in the 1991 documentary that one of the prayer’s themes was “Kiddush Hashem,” literally the “sanctification of God’s name.” The phrase is often used to describe self-sacrifice for the greater good.

“I think Kiddush Hashem exists not only for religious people, and that the cemeteries over 100 years of Zionism are mostly evidence of Kiddush Hashem on the part of parents who buried children because a young son gave his life for something that was more important to himself than himself,” Ben-Gurion said. “That is why this tune will continue to speak, and will outlive its time and its words.”