Working and Fighting for a Homeland for My People

By Eric Gartman

Jewish refugees in the barracks at Feldafing displaced persons camp. Germany. The overcrowded conditions are clearly visible in this picture. There were only three toilets for the nearly two thousand people. They lived ate, and slept on double decker beds and cots with no room for the clothes and personal items. “As far as the eye could reach stretched this sea of men and women sitting on cots, staring silently at me,” a visitor wrote. “One could sense an air of resignation.”

Passover tells the story of the Exodus from Egypt, when the ancient Israelites returned to the Promised Land. But within the last generation, another exodus took place. This time the shattered remnant of the Jews of Europe returned to the Jewish homeland after the Holocaust.

Like their ancient ancestors, their journey was a treacherous one. Whereas the ancient Egyptians had tried to prevent the Hebrews from leaving, after World War II, the British tried to prevent their descendants from entering their homeland where they might finally live free from persecution.

During the three years after the end of the Holocaust and the Second World War, hundreds of thousands of survivors, homeless, destitute, with no families left, languished in displaced person’s camps in post-war Europe. The conditions in these camps were deplorable. Ira Hirchmann, an American Jew, saw the filth and squalor firsthand at one such facility in Germany. The Jews were housed in a three-story cement garage, used by the Germans to store coal and lumber. He found 1,800 men and women living there “like cattle in an abattoir.” There were only three toilets for the nearly two thousand people. They lived ate, and slept on double decker beds and cots with no room for the clothes and personal items.

“Although my first impulse was to run from such a revolting scene,” Hirchmann admitted, “I forced myself to circulate through the narrow spaces between cots and to try to understand how people could remain alive and human when forced by civilization into a subhuman state.” What he saw shocked him: “As far as the eye could reach stretched this sea of men and women sitting on cots, staring silently at me. It was late afternoon. The rain and wind blew in fitfully through the glassless windows; the odor of heavy, sweat-drenched clothes, of unwashed bodies, of the dankness of cement floors and walls, and above it all the stench of urine and human excrement, was overpowering…Some of those wretched souls clutched at me as I passed, seeing that I was a stranger; perhaps someone who might help.”

These survivors wished to flee Europe for Palestine, the Land of Israel where the Jewish nation was being reestablished after generations of exile. “Poland held too many bitter memories for me,” one survivor explained. “I despised the resentment of the people towards the pitiful handful of Jews who had survived the Hitler period, and I was sickened by the attitude of the Polish Government officials, who pretended that anti-Jewish sentiment did not exist.” Instead, he explained why he wished to go to Palestine: “For me, a homeland for the Jews seemed the only possible answer.”

All other nations had homelands, and it seemed in the wake of the Holocaust that the only way to ensure Jewish safety was through a Jewish state: “I was steadfast and determined in my desire to leave Poland, to reach Palestine, and to join with Jews from all over the world in working-and fighting-for a homeland for my people.”

David Ben-Gurion delivers a speech at the Zeilsheim displaced persons camp. “He was the embodiment of all their hopes and aspirations. The black night was over, and the first rays of a new dawn were bursting over the skies of their miserable camp. The displaced persons (DPs) sang, cheered, and wept as Ben-Gurion told them they would soon come home to Zion.”

David Ben-Gurion himself went to assess the situation in one camp. An American Jewish chaplain named Judah Nadich drove Ben-Gurion to a displaced persons camp near Dachau. The inmates erupted when they saw him, even though they did not know he was coming. Nadich wrote:

"Suddenly, one of the Jews...happened to peer into my automobile and, recognizing the strong face and the white shock of hair, suddenly screamed in an unearthly voice, 'Ben-Gurion! Ben-Gurion!’ Like one man, the entire group turned toward the car and began shrieking, shouting the name of the man who was accepted by all of them as their own political leader."

Nadich assembled the inmates in the camp auditorium. Then came the great moment: He led Ben-Gurion into the packed auditorium. Every seat was taken, the aisles were full. The hall overflowed, those who couldn’t get in stood by the doors and leaned into the windowsills. As Ben-Gurion entered the crowd erupted in song –Hatikvah – the hope, the Zionist anthem.

David Ben Gurion, who was to become Israel's first Prime Minister, reads the Declaration of Independence on May 14, 1948: “It is the self-evident right of the Jewish people to be a nation, as all other nations, in their own sovereign state. By virtue of the natural and historic right of the Jewish people and of the Resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations, we hereby proclaim the establishment of the Jewish State in Palestine to be called Israel.”

“The hope that had never died, the hope that was unquenchable in their breasts, the hope that had kept them alive,” Nadich explained. “As Ben-Gurion stood on the platform before them, the people broke forth into cheers, into song, and finally, into weeping. For the incredible was true; the impossible had happened. Ben-Gurion was in their midst and they had lived despite Hitler, the Nazis, and all their collaborators, with all the diabolical instruments of destruction at their command—they had lived despite them all to this day when they could welcome Ben-Gurion!”

He was the embodiment of all their hopes and aspirations. The black night was over, and the first rays of a new dawn were bursting over the skies of their miserable camp. The displaced persons (DPs) sang, cheered, and wept as Ben-Gurion told them they would soon come home to Zion.

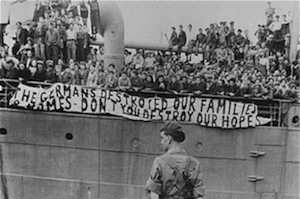

But the British, sensitive to the desires of the Arabs, refused them entry. The ragged survivors would not be denied, however. With the British refusal to allow Jews into Palestine, the refugees began to take matters into their own hands. Aided by the Jewish Brigade and the Mossad, the Israeli intelligence service, the refugees began to seek to enter Palestine clandestinely.

The operation was known as Bricha (escape). Establishing a network of safe houses and schools, the Bricha bribed border guards, taught the refugees Hebrew, and brought them from the camps to ports in the Mediterranean where they were crammed onto ships bound for Palestine. In the three years after the end of the war, thirty-five ships and over 50,000 refugees attempted to enter Palestine. Most were stopped by the British navy, and their passengers interred in camps on the island of Cyprus. Golda Meir went to see the camps for herself. She was appalled by what she saw:

Water being distributed at Cyprus refugee camp. Each resident was allowed only two pailfulls. “There wasn't nearly enough water for drinking and even less for bathing, despite the heat,” Golda Meir wrote. “They looked like prison camps, ugly clusters of huts and tents—with a watchtower at each end-set down on the sand, with nothing green or growing anywhere in sight.”

The camps themselves were even more depressing than I had expected, in a way worse than the camps for DPs that were being run in Germany by the US authorities. They looked like prison camps, ugly clusters of huts and tents—with a watchtower at each end-set down on the sand, with nothing green or growing anywhere in sight. There wasn't nearly enough water for drinking and even less for bathing, despite the heat. Although the camps were right on the shore, none of the refugees was allowed to go swimming, and they spent their time for the most part, sitting in those filthy, stifling tents, which, if nothing else, protected them from the glaring sun. As I walked through the camps, the DPs pressed up against the barbed-wire fences that surrounded them to welcome me, and at one camp two tiny little children came up with a bouquet of paper flowers for me. I have been given a great many bouquets of flowers since then, but I have never been as moved by any of them as I was by those flowers presented to me in Cyprus by children who had probably forgotten—if they ever knew—what real flowers looked like.

Meir was shocked that the Holocaust survivors were being locked up again under conditions that were little better than the concentration camps. But the fate of another refugee ship would change the modern Exodus and end the exile of Jews from their homeland once and for all.

CONTINUE TO PART 2 »

Born in Israel to American parents, historian Eric Gartman never lost his fascination for the Jewish homeland. He is the author of Return to Zion: The History of Modern Israel, (2015), a critically-acclaimed narrative of the birth and survival of the Jewish State.

Recommended for you:

YOUR ISRAEL CONNECTION FOR PASSOVER

Bring Israel into your Passover Seder today!

About the Author