Unity without Uniformity: Learning to Love the Jews Again

by Bradley Shavit Artson

Secular and ultra-Orthodox protesters arguing in Beit Shemesh.

Copyright © Olivier Fitoussi

It’s getting harder and harder to love the Jews. Or, to put the matter more precisely, its getting harder and harder to love those Jews who aren’t just like us.

Many among the Orthodox feel that the rest of the Jewish community is obsessed with bashing Orthodoxy and abandoning Torah. The non-Orthodox feel that the state of Israel, under the sway of the Orthodox, is delegitimizing other forms of Judaism while falling prey to narrow party politics, and that the official spokesmen of Orthodoxy offer a crude caricature of other forms of Judaism and their adherents. Every Jewish group squawks like a victim, and that’s a dangerous tone to adopt.

Victims can cultivate their rage without limit; and they can contemplate how to seek retribution without concern. If every Jew feels like a victim, then prepare for civil war.

However deep our wounds, however strident the rhetoric, it is not to late to step back from the brink, to affirm our unity and our desire for connection with each other. In the service of Jewish unity, for the sake of Zion, I offer a few responses to some of the primary gripes of victimhood that plague our people today. Things are not as bad as they seem.

There’s no longer any common ground between the Judaism of Orthodoxy on the one hand, and the Judaisms of Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist, and Renewal on the other — it’s just ‘them’ and ‘us.’ On the surface, there is a real substance to this feeling: Orthodox Judaism has produced communities that really do observe Shabbat and the festivals, really do keep kosher and study Torah. Its scholarship has produced translations of Talmud and Mishnah and many guides to Orthodox thought and practice. 20,000 Orthodox Jews gathered to celebrate a seven year cycle of reading the entire Talmud, an event impossible to attain in the non-Orthodox world.

Anat Hoffman, a leading member of secular Jews community who is currently lobbying for lifting the segregation of women in buses says we just want equal rights for every Israeli.

Non-Orthodox Judaisms, on the other hand, have produced great passion and innovation in advancing egalitarianism and applying the wisdom of Judaism to many of the pressing social and intellectual issues of the day. Its scholarship has produced translations and critical editions of midrash, philosophy, theology and have utilized secular learning to broaden our understanding of Jewish living and Jewish values (producing the kinds of creative studies that don’t emerge from Daf Yomi learning). And its rabbis are leaders in the larger communities, often authors of creative and popular books, active in shaping the organizations and responses both of the Jewish and the general populations.

The agendas of the different communities looks disparate, and their practice of their heritage seems far apart. Do we have anything in common any longer? There are two helpful ways to consider Jewish unity: heritage and destiny.

Our heritage — the building blocks from which we construct our Jewish identity — is identical. We read the same Torah (although we interpret it differently), the same prophets, the same Psalms. We quote from the same Talmud, Midrash, philosophy, and poetry. Despite many differences, one is struck by how similar our liturgy remains (often to the frustration of more radical members of the liberal movements). Our roots are the same, even if we do filter our understanding through different contemporary lenses.

On the matter of heritage, Jewish unity is quickly apparent. That unity is also clear in terms of destiny: we share a common future. Prominent anti-Semites don’t distinguish between the observant and the non-observant. The serious challenges facing the Jewish world — the security of a vibrant, democratic Israel, the survival of Diaspora Jewry, the struggle of oppressed Jewry, strengthening the connection between the Jewish people and Judaism — those issues cross denominational lines. Either we will address those issues together, or we will fail together. No group is exempt from the challenges and strains of our age. Our destiny remains, quite literally, in each others’ hands.

Reform, conserative, orthodox Jews, in one table

Copyright © Noam Galai

Look at all the areas in which Jews cooperate across denominational lines: in federations and Bureaus of Jewish education, rabbis and educators of all stripes work together, and lay leaders of the different denominations sit through countless committee meetings for the good of the entire Jewish people. At universities, professors of Jewish studies learn and teach with colleagues and students regardless of denominational affiliation or loyalty. Major Jewish publications: Moment, Tikkun, Commentary, Sh’ma, the Jewish Spectator, regularly feature writers from each of the different branches of Judaism today. Community Jewish newspapers routinely report on the happenings of all Jewish groups within their region. And on a non-institutional level, friendships and collegiality is the norm among Jews who work together on the job and who live together as neighbors.

If the problem isn’t one of a lack of common ground, if by heritage and by destiny we are still united, then perhaps the problem is to be found elsewhere? Maybe the problem is one of ideology. That leads to a second objection:

Orthodox Jews don’t think that other Jews are authentically Jewish. Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist, and Renewal Jews don’t think the Orthodox are ethical or broad-minded.

It is true that we Jews are quick to stereotype each other. Orthodox spokesmen accuse non-Orthodox rabbis of being “clowns,” and assert that the other movements have abandoned Torah or trimmed it to suit their faddish fancies. Leaders of non-Orthodox movements hurl back that the Orthodox are medieval (is that really such a bad thing to be?) superstitious, and concerned only with ritual punctiliousness rather than with the glorious ethical mandates which animate Jewish tradition.

In these charges we hurl at each other, there is just enough truth on both sides to make us all uncomfortable. But it isn’t hard to perceive the aggrieved voice of the victim, seeking to salve its own wounds by inflicting harm on others. Stereotyping each other is ultimately not helpful: it doesn’t strengthen our own Judaism and it doesn’t assist other Jews in understanding us any better.

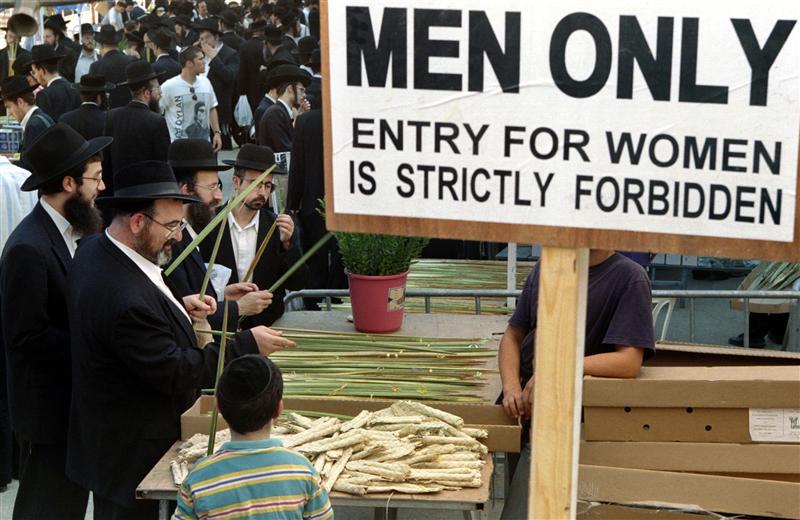

Secular Israeli women performing a dance protest against the exclusion of women in Beit Shemesh

Let’s be clear on one thing, Jews have always argued: Isn’t it true that throughout the millennia, different Jews have accused each other of distorting the true essence of the faith? In the First Temple period, kings, priests, prophets, and the people hurled the strongest sorts of charges at each other. Defining who was a “troubler of Israel” depended very much on one’s vantage point, but the Judaism of that founding age was hardly one of unity and peace. In the Second Temple period, things hadn’t changed much: Pharisees, Sadducees, Zealots, Essenes, and the Amei Ha-Aretz each had very different notions of how Judaism was to be observed, and the level of animosity and violence between those groups was often uncompromising and harsh. In the Talmudic and Geonic period, the Jews of Bavel and those of Eretz Yisrael argued in very strong terms, as did the Rabbinites and the Karaites. That factionalism continued in the medieval period, when French rabbis actually excommunicated Maimonides because they found his philosophy incompatible with their own understanding of Judaism!

The modern age is one that also revealed deep rifts, many of which had nothing to do with our own current denominations: the Vilna Gaon excommunicated the Hasidim, who warred against the Mitnagdim. Zionists and Bundists, liberals and neo-conservatives — ours has always been a contentious people.

Contention is part and parcel of taking ideas seriously. Woe to the Jews when we no longer think our ideas and opinions are worth a good argument. The truth is we do have deep and profound areas of disagreement in the realm of theology and practice. And those differences cannot be swept away (nor should they be minimized). But the correct response to different opinions is more discussion. By all means let us seek to persuade each other of the best (in our opinion) way to be serve God and live Torah. “Come, let us reason together, said Adonai.” Good advice then; it is good advice still.

To meet and share in that way doesn’t require the conferral of authenticity or the recognition of intellectual openness. All it takes is a desire to be together, a willingness to listen to each other, and an ability to express disagreement in a caring and constructive way. Jews still do that all the time, regardless of the unfortunate remarks that capture the headlines.

We are heading toward a time when Judaism will be bifurcated into two religions.

This threat is real. If we don’t learn to speak respectfully about each other, if we cannot express the important areas in which we differ with dignity and caring, then we will indeed shatter the unity of the Jewish people. There is a difference between unity and uniformity. We have never been a uniform people (we care too passionately about God, Torah, mitzvot, and tikkun olam to be indifferent on those points). But we have been able to maintain unity despite our uniformity. That need is still the demand of the hour.

The Mishnah extols the greatness of the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai: that despite their strident differences of opinions over fundamental matters of halakhah, each would eat in the others’ houses (often requiring sages to eat food that was ritually impure by their own understanding) and they would marry into each others’ families. That model, mipnei darkhei shalom, for the sake of peace, ought to be our own today.

On a personal level, what that means is that for the sake of Zion, I cannot allow my passion for Conservative Judaism to allow me to denigrate the life paths of my fellow Jews. That I have found a spiritual home and an intellectual haven is a blessing for which I thank God and those bold sages who enunciated an expression of Judaism so congenial to my soul. But that happy recognition ought to impel me to recognize other forms of Judaism as providing those same blessings for my fellow Jews. I should rejoice on their behalf. I don’t have to agree with their theologies, I don’t have to embrace their policies, and I don’t have to silence my dissent. But, for the sake of my own soul, I do need to recognize a blessing when I see it.

Beyond our disagreements, we did all stand together at Sinai a long time ago. And in the messianic future, the entire Jewish people will be ingathered: all together, or not at all.

In the interim, perhaps, we should work a little harder at treating each other with a modicum of dignity, restraint and, dare I say, love?

Ahavat Yisrael is after all, a mitzvah.

Bradley Shavit Artson is Vice President of American Jewish University and Dean of it’s Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies, is the author of The Bedside Torah: Wisdom, Vision, and Dreams (McGraw-Hill) and Jewish Answers to Real-Life Questions (Alef Design).

Recommended: