Purim Lessons for Today

By Rabbi J. Rolando Matalon

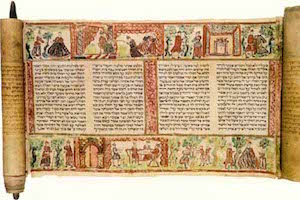

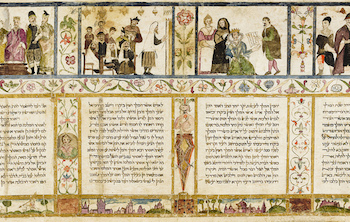

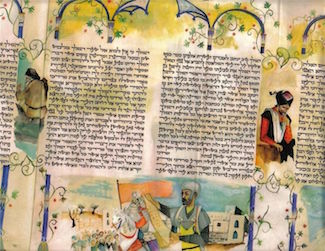

Illuminated Scroll of Esther, early 17th century, Ferrara, Italy. Photo by William Gross

God’s name appears nowhere in Megillat Esther. Singular among the books of the Bible, the Book of Esther masterfully delivers the combined explosive energies of laughter, randomness, sexuality and violence. But it never delivers God’s name. Yet, according to the sources (Midrash Mishle 9:2), Purim will remain a holy day forever, even as all the other holy days will be abolished in the World to Come.

What then is so holy about this godless celebration of intoxication, frivolity and irreverence? The meaning of Purim is to be found precisely in the idea of concealment, and particularly of God’s deep concealment. Esther’s name means “hidden” and her identity remains secret. We too hide our identities as we dress in costumes and mask our faces. But the word megillah (scroll) is connected to the word megaleh which means to reveal. Purim, then, is about searching below the surface—the invitation to pierce through randomness, vulgarity, and violence in order to uncover meaning and God’s Presence.

Reflecting on the obligation to get drunk on Purim, Rabbi Meshulam Rath (1875-1963), author of the book Kol Mevasser, offers this very perceptive teaching: “Rabbi Bunem comments on the statement of the Zohar that Yom HaKippurim (Yom Kippur) is ‘like Yom Purim’ (keYom Purim) by indicating that Yom HaKippurim depends on Purim. Therefore Purim is superior to Yom HaKippurim. Rabbi Bunem says that on Yom HaKippurim we afflict our bodies, while on Purim we afflict our mind. Our Rabbis teach in the Talmud (Megillah 7b) that a person is obligated to drink on Purim to the point of being unable to distinguish between ‘cursed be Haman and blessed be Mordechai,’ and afflicting our mind is a greater challenge than afflicting our body. And for this reason Yom HaKippurim depends on Purim.”

IDF soldiers celebrating Purim - photo courtesy of IDF on Twitter/X

Purim is the holiest of our holy days because it demands that we mobilize our deep hidden resources, that we pierce through mindlessness and through the moral confusion of good and evil, in order to reach the divine.

Purim is the climax of the festival cycle that begins with Pesah in the first month of the year. The story of Pesah is the story of how God takes us by the hand and redeems us from Mitzrayim, from the narrow places where we get stuck and suffer. God then leads us through the wilderness while providing for all our needs, giving us guidance (Torah) and protection.

The goal is that we will gradually learn to be independent, that we will internalize a moral compass and God-consciousness through the study and practice of Torah. The goal is that we will learn to reach redemption and God’s Presence on our own. That is why Purim is the last holy day of the year: Purim is about humans taking full responsibility and taking their lives into their own hands. Purim is about the miracle of human self redemption. When we struggle to take ourselves out of the narrow places where we get stuck and suffer, when we learn to make light in the darkness is when we meet God’s concealed Presence.

Times have been quite dark for the world in general and for the Jewish people in particular beginning several years ago—just as we entered into a new century—and culminating a few months ago. I do not need to repeat here the litany of calamities and scandals from wars to financial collapse to Madoff.

Our misfortunes have revealed a serious failure of morality and a collapse of values, both in the public and the private domains. We have been intoxicated with materialism, arrogance, excess and frivolity; these are at the top of the list. We have all been caught in the wave of mindlessness in one way or another. No divine hand will come to rescue us this time. It is imperative that we recover the moral compass that is already ours and begin the work of self redemption. Trying to understand the meaning of Purim may be a place to start.

José Rolando Matalon, B’nai Jeshurun’s Senior Rabbi, was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina and was educated in Buenos Aires, Montreal, Jerusalem and New York City. Rabbi Matalon’s involvement in the New York, Jewish, and Israeli communities is broad and deep; he serves on a number of boards, including the Advisory Board of T’ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights, the Advisory Board of Beit Tefillah Israeli-Tel Aviv, and the Leadership Council of Habitat for Humanity. He has received awards from the New York Board of Rabbis, the Jewish Peace Fellowship, and the New Israel Fund.