How Can Parents Help Children Cope With Trauma?

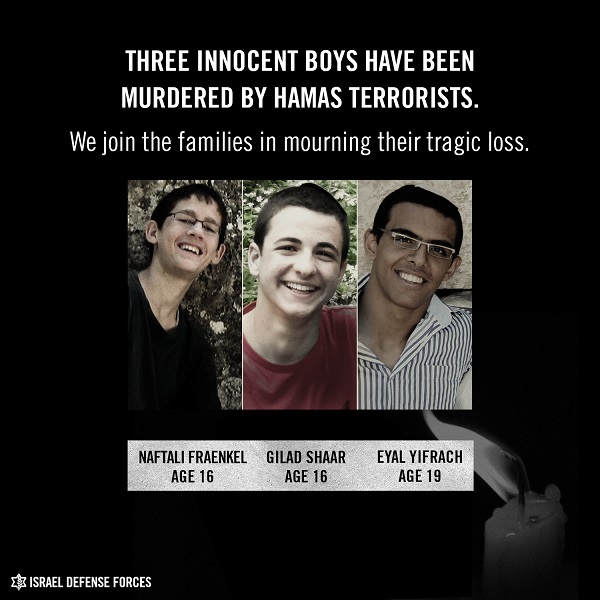

Thinking about what I might contribute in the wake of the horrific 2018 shooting in Pittsburgh, and now as the horrible attacks against our nation continue, I vividly recalled the morning after the bodies of three kidnapped boys – Gil-ad Shaer, Naftali Fraenkel, and Eyal Yifrah – were found after an intense and hopeful search. I was in Israel that summer and sitting with the mother of a four-year-old; she asked me, “What do I tell my son?”

For eighteen days, he and his classmates in the gan (pre-school) prayed every morning for the safety of the lost boys. Not wanting him to hear from his classmates that the boys had died, she told him that the lost boys were not coming back. Another woman told me that she wished her young son’s school had told him about the murders because she herself was afraid to tell him about the tragedy.

Unfortunately, we are seeing that terrorism and mass violence are indiscriminate; these attacks can happen anywhere and to anyone at any time: soldiers hitchhiking at a bus stop in Gush Etzion, patrons eating at a café in Paris, children watching The Lion King at a New York theater, fans waiting at the finish line of the Boston Marathon, high school students attending classes in Parkland or Santa Fe, music-lovers listening to a concert in Las Vegas, or worshippers praying with their congregations in Charleston, Sutherland Springs, or in Pittsburgh.

As parents, we grapple with how to help our children cope with horrible news, especially while we, at the same time, try to work through our own anxiety, pain, and grief. The advice I received then, is still relevant now.

The experts agree that children need to hear such news from an adult with whom she or he has a close and comfortable relationship, preferably in a familiar setting – home if possible – and if it is comfortable for the child, to touch and hold her or him. Actively listen to your child and be aware and sensitive to your child’s responses.

While it is important not to avoid these difficult conversations, it’s alright not to know the answer to every question and to be honest with your child and learn together. At the same time, children’s exposure to television programs and social media, especially to scenes of the event and its aftermath, should be monitored and limited.

I asked Dr. Naomi Baum, former director of the Resilience Unit at METIV: The Israel Psychotrauma Center, what these mothers should do, first with regards to the Israeli boys’ vicious deaths. She answered that “The children need to be told the truth – that the boys were murdered, not just that they weren’t coming home.” She then elaborated more generally:

"We know that children’s response to terror is closely related to how the adults in their environment – parents, caretakers, teachers, youth counselors, grandparents and more – are responding. If the adults are hysterical, it is likely that the kids will be too. The younger the child, the greater the impact will be of those adults in his/her environment.

"Therefore, it is most important for parents to maintain a calm, loving presence on the one hand; and on the other hand, to make sure that the lines of communication are open so that there can be honest discussion about what is going on and kids will feel free to both express their feelings, and ask questions.

"It also is important to remember that all feelings are legitimate, and no feelings should be dismissed or judged inappropriate.

"Lastly, it is important to take in to account the developmental stage of the child, and use concepts and terms that are familiar to him or her."

According to Baum, “Talking about difficult situations with kids is a skill that can be developed. One must start with facts and move on from there. It is not necessary to share with children every last detail. Each parent or adult needs to decide what and how much to share with the child. Parents need to remember that even though they may not talk with the child about what is going on, he or she will likely hear in the school yard or via a friend what has happened. Thus, if the parent wants to have input, he or she must talk with the child.”

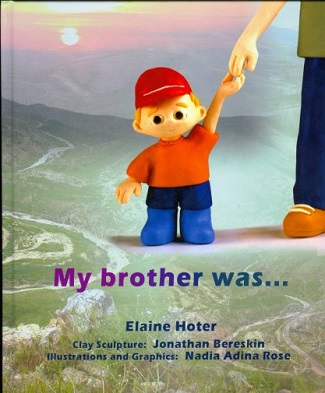

Elaine Hoter of Alonei Habashan in the Golan Heights understands this and speaks from the perspective of an educator and as a mother who has been there. Her seventeen-year-old son Gavriel was murdered by two terrorists at his yeshiva in Israel in 2002. From the beginning, Elaine, her husband Chaim, and their five surviving children did not take Gavriel’s death as their own personal tragedy, but as a national tragedy.

Learning first-hand that people do not know how to react to bereavement and loss, Hoter has taken on a mission of helping others understand, particularly people who are so frightened of death or frightened to go to a shiva. She supports other families bereaved by terror and speaks to diverse groups in her home and across the world.

Hoter also has written a book to help other children who have lost a brother, like her youngest son who was four at the time of Gavriel’s death. My brother was… (Israel: Midreshet Gavriel, 2005) expressively and movingly describes the way young children cope with loss and mourning.

The book tells the story through her young son’s eyes – everything he went through and the stages that children go through. Things they normally can’t talk about with their parents because parents don’t understand what they are going through. Hoter now advises other parents and educators that: “On the one hand we want to encourage empathy in our children with the victims and the families and make them feel part of our nation, but on the other hand we don’t want to scare the children and cause bad dreams and fear.”

She continues: “I think the key is that you don’t have to tell the children everything. Keep out the graphic details. Paint a picture that we have a strong army and security forces – policemen, security officers, etc – who do everything possible to keep us all safe. There is a difference when the child is directly affected by the event, if they were a witness to an attack or it happened within their family circle. As with adults each child has their way of coping, some like to hear stories, others like to listen to music or use clay to show their feelings or paint. As parents we often know which is the best means for each of our children to cope with the trauma.”

These principles are the same for all types of trauma, wherever they occur:

- Tell children the facts, without being graphic

- Children should hear the facts from a grown-up they can trust and have a good relationship with. Use age appropriate language and, when appropriate touch (a hug, hold hands) can provide a comforting counterbalance to hearing difficult words.

- Stress real and true actions being taken to solve the problem so that children feel as safe as possible such as, “police (or other security forces) are working to protect us, stop bad people” or any other examples that might be relevant to your situation.

- Remember that no emotions are wrong in a traumatic situation! Some children might prefer to talk about their feelings, others might prefer to draw, dance or hit a punching bag.

- One of the best ways to empower a child after a traumatic experience is to provide an activity they can do to help the people affected. The Israel Forever Letters of Friendship Initiative is an easy activity to do with children of any age where they can be empowered by offering comfort to others who have also endured trauma.

Dr. Ruth Pat-Horenczyk and her colleagues at METIV support this advice and add the importance of play and playfulness in the development of children under normal circumstances, and most especially in the face of terror or even bullying, they serve as a protective factor under traumatic circumstances to counteract feelings of depression, anxiety, and panic, as well as give them the opportunity to create meaning in various ways.

Although difficult situations can have negative consequences, at the same time they can also have positive outcomes. Being hopeful, keeping a positive attitude, and looking forward to the future will help our children cope now and help them grow into resilient and caring human beings in the future.

In times of adversity and turmoil, as parents, we are in the best position to help our children. To help us prepare and respond, the following resources may be helpful for parents when talking to children about terrorism, mass violence, and antisemitism. While we encourage parents to listen to their children and to not avoid having these difficult conversations, they also remind parents to take care of themselves and to consult with trusted professionals in the field for further guidance if necessary.

THOUGHT QUESTIONS FOR PARENTS:

- Who best should address mass violence incidents with children and why?

- How do you think parents can address mass violence incidents with their children?

- Which of these tips resonate with who you are and how you act as a parent?

- What are you doing to help build preparedness and resiliency within your family and children?

- What additional resources might be helpful for you if you and your child should be faced with another traumatic event?

READ MORE Resources:

- METIV’s Articles for Children and Adults Helping Kids Cope with Trauma

- METIV’s 9 Ways to Support Children After a Traumatic Event

- NATAL’s Supporting Your Children in Times of Stress

- Helping Children Cope With Terrorism - Tips for Families and Educators

- Helping Children Cope with Frightening News

- AAP’s Talking to Children About Tragedies

- PJ Library’s How to Talk to Your Children About Anti-Semitism

- Reform Judaism’s Jewish Resources for Coping with Acts of Terror

- How to talk and make a Difference when coping with terrorism

- Terror, Media and Children

- Helping Children Cope after a Traumatic Event

- Talking to Children about Events in Pittsburgh

- Disaster Response and Recovery Information

- USCJ Parent Guidelines for Helping Youth After Mass Violence Attack

- Creating a Secure Bedtime Routine to Ease Your Child's Anxiety

Recommended for you:

About the Author