A Fork in the Road: The Uganda Scheme

By Jason Blau

Herzl at the Sixth Zionist Congress

On August 23, 1903, Theodor Herzl had an announcement for the Sixth Zionist Congress. Finally, the Jewish people had been given assurance, for the first time in over a millenia, that a polity of their own could be created. The British Empire, no less, the greatest of the great powers, had made such a momentous offer. However, there was a catch.

This new polity was to be in East Africa, not Zion - the historically recognized Land of Israel, homeland of the Jewish People. Known as the Uganda Plan, it is often forgotten, a tale that fails to fit any narrative, and seems an absurdity to most. However, this proposal was seriously considered. In fact, many thought it made perfect sense, and it ended up creating a long and damaging rift in the Zionist world for many years to come.

In order to understand how this came about, we must backtrack to 1895. In that year, the Uganda Railway was completed. An enormous expense, the railroad was an ambitious project that linked colonial Mombassa, to the newly held British territories in the African Great Lakes. Joseph Chamberlain, then Secretary of the Colonies, championed the idea, and despite enormous negative press due to expenditure, several man-eating lions, and outbreaks of disease, it was completed.

Against Chamberlain’s predictions, however, this railroad did not immediately yield financial dividends, and the railway was starting to look like his personal albatross. Not to mention, he was facing problems with his working class voter base, as Jewish refugees from Russia began to arrive in Britain, stirring up anti immigration sentiment.

On the Zionist side, Theodor Herzl had been trying to obtain a Jewish state in Zion, and despite initial hopes, had found himself stymied by Ottoman reluctance to allow large scale Jewish settlement. The prospects he would soon report to the Zionist Congress meeting in Basel would not be encouraging. Combined with these factors, earlier in the year, a pogrom had racked the city of Kishinev, modern day Moldova.

Not just any pogrom, this one gained notoriety worldwide due to the extremely high death toll and the enormous number of Jewish homes destroyed. Many coming to the Zionist Congress had a strong belief that the essential part of the Zionist Progam was a Jewish sanctuary for immigration, resettlement, and safety. To them, any Jewish land was better than waiting out for an indeterminate amount of time . From their perspective, it was a matter of pragmatic concern for Jewish lives, and any land would do.

All these factors combined into one maelstrom, when Chamberlain realized he could solve his many political problems with a single plan, “Uganda Scheme”. The railroad’s prospects would be rescued by an influx of Jewish refugees settling along it, who would help British East Africa to prosper, while simultaneously removing the immigration issue from the minds of his constituents.

In short, Chamberlain had a chance to play the part of a humanitarian hero, look like a strong nativist to his working class base, and make good on his political investment in the railway. Herzl, alternatively, could find a sanctuary for the Jewish people, circumvent Ottoman refusal to allow substantial Jewish immigration, and present a concrete proposal to the Zionist Congress in face of the Kishinev Progrom.

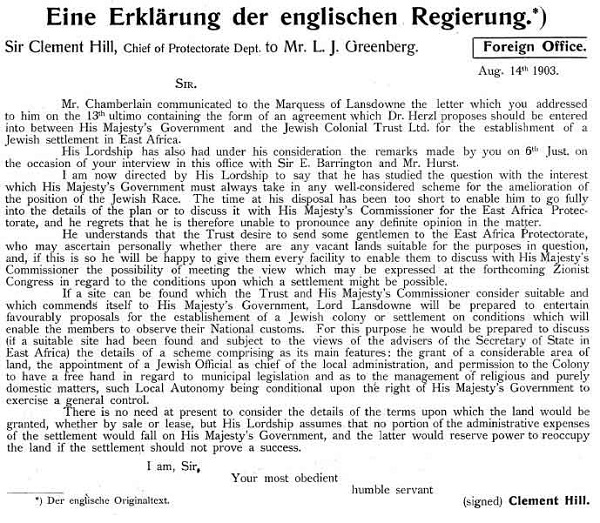

The Uganda Proposal from the British Government, 1903

As smooth of a solution as this likely sounded to Herzl and Chamberlain, proposing that the new Jewish home would be set up in the highlands of East Africa was sure to be controversial. And so it was. The debate over whether to send a commission to simply examine the territory became a vitriolic dispute in which ⅓ of the entire Congress ended up walking out after the surveying expedition was approved.

This minority saw the proposal as extremely dangerous. With the Ottoman Empire banning any large scale immigration, and a solution to the “Jewish Question” being presented, many saw this proposal as dooming the concept of a return to Zion. While it was seen as temporary expedient, inertia has a life of its own, and it might simultaneously reduce the impulse to found a Jewish home in Zion, while the land in question, without the same connection to Jews, might never attract a large number of immigrants.

However, this, of course, did not come to pass. While the debate was reaching a fever pitch in the Jewish political life of Europe, including an attempted assasination of Max Nordgau, an ally of Herzl and cofounder of the World Zionist Organization, the expeditionary members were incompetent.

They reported back to the Seventh Zionist Congress the following year, the region was an unproductive wasteland, unfit for large scale human habitation. In contrast to the predictions made by previous surveyors, or the evidence of today, in which the Mau Escarpment of modern day Kenya, is considered the breadbasket of all of East Africa, the expedition declared it completely infertile for large-scale farming.

While many historians wonder how they got to such a conclusion, some even proposing that the surveyors were secretly allied to the anti-Uganda faction, it naturally put an end to the discussion. Zion was to be the goal. This brief foray into exploring other options for a Jewish homeland, and its resulting, and embarrassing, failure, ensured that from now on, the Zionist Organization was to look only towards Israel.

Both Joseph Chamberlain and Theodor Herzl died in the wake of the debate, never to see the results of their efforts. Let us be thankful that the plan failed as it did. Who knows what would have become of a Jewish homeland in modern day Western Kenya. However, one suspects that it never could have attracted too many Jewish immigrants, contrasted with the lure of economic prosperity and comfort in the United States, Canada, or Argentina.

With it, doubtless the push for Israel would not only have been weakened, but it is much more difficult to imagine the British making a second commitment to a Jewish homeland, in the Balfour Declaration. Even if such a statement had been made, the resulting formation of the Yishuv would have been much weaker, seeing as how many of the first generation of pioneers would already be in East Africa. Again, one cannot ever have certainty about such a topic as alternate history.

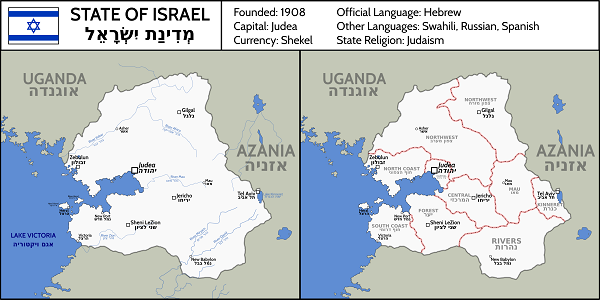

Alternative history map of Israel based on the Uganda scheme, posted to r/imaginarymaps

This oft forgotten episode in Jewish history serves as both an interesting tidbit for speculation, and a milestone for the creation of Israel. It serves not so much as an important event in its own right, but demonstrates its importance as a non-event. The Uganda Scheme’s early and inglorious failure, refocused the Zionist movement for a homeland in Eretz Yisrael, of which we still reap the fruits of to this very day.

Recommended for you:

Herzl's dream was partially fulfilled with the creation of the State of Israel, but it has not yet been completed. Come engage with one of our great leaders of Jewish history!

How are you Living the Legacy?

About the Author