A Struggle for Survival: A Testimony of Life on Exodus 1947

Tova Ben-Menachem (Giza Mandel)

Prepared by her granddaughter, Maayan Kabli

The good days passed quickly. One morning we were given khaki colored uniforms with caps shaped like boats and the girls were told to embroider the words “Exodus 47″ on the right side. We weren’t told the meaning or significance of the word and we didn’t ask. We carried out the order and we were photographed for the last time in the institute, wearing the uniforms. The next day army trucks rolled into the institute and, without explanation or indication of where we were going, we were ordered into the trucks.

We still didn’t know where we were headed when we finally reached the train station. We were told to get out of the trucks and to board the train. We were really happy – a real passenger train! And there, facing the door of the car in which I sat with my sister, I saw my parents, both of them crying, and then we were told that we were on the way to Eretz Israel and they told us that they knew of the plan to send children to Israel on their own, with the parents joining them several weeks later, after arriving on a different ship. But the Sochnut [Jewish Agency for Palestine] disappointed the unfortunate parents, because there was no such plan for them. The real plan was to send 4,500 children, together with a few elderly people and young pregnant women, all of us holocaust survivors.

The train moved; my mother had enough time to say to me, “Take care of your sister, even though she’s older than you are.” And I kept my promise. After running for a few hours the train stopped and we were transferred to trucks. We stopped somewhere in the countryside. Once again a camp, this time in in a French village. I heard a language I couldn’t understand. When I had walked around the camp, which was surrounded by a heavy wire fence, I saw trees on the other side of the fence with fruit that I had never seen before, while underneath them women picked the pretty but strange fruit that stirred my appetite. They still hadn’t quieted the hunger that gnawed at me relentlessly from within.

They housed us in small rooms, in temporary buildings that had apparently been built just for us. They prepared us in advance to be awakened suddenly at different hours of the coming nights and in the few minutes we had available we had to pack only the most essential clothes in small backpacks that were no wider than the span of our shoulders. Right from the very first night, when the siren sounded we ran out with our backpacks, where we were faced by reality. We had to pass between two walls that had been built for the training exercise, approximately the width of our shoulders. This was the width of the passages in the ship, After several trials, at the moment of truth we had to throw away our backpacks and in their place dress ourselves in several changes of clothing. The rest remained behind. The next night we boarded the trucks and at dawn reached the port called Pirten 1, but didn’t enter the port. We boarded the ship on strong planks that crossed over a raft.

Everyone moved in exemplary order, silently, in Indian file and with great caution, because nobody wanted to fall into the water. The passages inside the ship were narrow and I understood immediately why we couldn’t bring our backpacks with us. The ship’s interior was lined with wide shelves that served us as beds. We had to lie on our sides, packed closely together. The situation was that when one wanted to turn over all the others had to turn over, too.

We were still far from desperation, because we knew that in about a week we would reach the shores of Eretz Israel!

I longed for water, for a shower to give me some relief from the harsh feeling that enveloped me. Was it possible that the ship had no shower? I began to look into it despite the fact that walking around the ship had been strictly forbidden.

I was an alert girl. I saw what others didn’t want me to see and I heard what they didn’t want me to hear. When my suffering reached its peak, I disobeyed the order. I slid from the shelf, that is from the sweaty bed, seeming but invisible to others. I began to crawl between the rows until I reached the place where they had hung a rope ladder that descended to the bottom of the ship into a maze of pipes and apparently machines as well. I began to wander around the area until I reached the prow of the ship, facing a big door.

In the background I heard the sound of men’s voices, apparently of the ship’s crew. Heavy steps were heard approaching the big door. I quickly flattened myself against one of the three doors and couldn’t believe what I heard: water! I stood there for several long minutes before I understood that this was the crew’s shower room.

While I was still standing there and waiting, a fat man wearing only pants and a chef’s hat on his head appeared and opened the big door. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing: two whole quarters of beef hanging from hooks and hundreds of tins of food such as juice and the like, and the word “food” escaped my lips. So much food and I was so hungry. Then I asked myself, what does it feel like to eat when one is full? Will such a day ever come?

In the meantime, an hour had passed and nobody had come to use the showers. I moved into the first shower, stood under the stream of water in my threadbare clothes and thought that in any case they would dry within an hour. The water was salty, but it was still pleasant to feel its coolness a bit. I kept the secret to myself.

I spent the following days, wandering about the ship, and even managed on occasion to go up to the main deck. I saw that there were two other ships, on either side of our ship: British destroyers with big cannons. I wondered what it all meant, why canons? Had the war begun again? The answer wasn’t long in coming. A few days later I noticed an unusual movement. All day long bigger boys and men carried loads on their shoulders – and there was no lack of older girls who also carried boxes of tinned food and all kinds of goods. I felt that something was about to happen. Awhile later, I heard sirens and an alarm. Shots were heard and two holes opened on the two sides of the ship. The water rushed in with enormous force.

The lower part of the hold quickly filled with water. There was real danger that we would sink. The water rose quickly. At that very moment hysteria and pandemonium broke out. Besides this, my older sister began to cry, “I want to drink, I want to drink!” I had no choice. I had promised my mother that I would take care of my sister throughout the trip. My mind worked quickly, I remembered the food storage room and the rope ladder that led down to it. I crawled quickly in the direction of the ladder, which was still in place.

I climbed quickly down the ladder, barefoot, with water already up to my hips. I went on quickly in total darkness in a race against time, groping in the darkness, bumping into pipes, falling, getting up quickly. Quickly, before it’s too late. I reached the store room. It’s door was open, as luck would have it. I quickly grabbed the first tin of food I could see, shook it to make sure it contained liquid and tucked it under my arm to leave my hands free. But the way back was almost impossible. The water had already risen almost to my neck. I saw death in my mind’s eye, yet my brain continued to give orders: “Giza, go on, don’t give up.”I found myself at the very opening through which the rope ladder had dropped a while back. But it was no longer there, I raised my head as much as I could and the tin was held firmly in my armpit. There are miracles on earth, it would seem.

Just then someone caught sight of me. It was our leader, Chaviva. I recognized her voice and she shouted, “There’s a girl here below. She’s drowning – throw a rope.” Someone did throw me a rope and she shouted again, “Grab the rope with two hands, otherwise I won’t be able to pull you up. Quickly, quickly.” But I only put out one hand because I held the tin under the other arm, and she shouted again, “The other hand,” but I remained as I was and for lack of choice they pulled the rope up with me hanging on to the end of it. My arm didn’t fail me and I fell onto the deck. I collapsed and the tin rolled out from under my arm. Someone opened it out of curiosity, because they had all been given cold water by the British who had rushed in through broken windows with cans of water. Everyone, including my sister had been given water – everyone except me.

The tin contained only tomato sauce, for which I had almost given my life. On deck a battle was still raging, sounds of gunfire in a real war. Commands in English and Hebrew were heard. We breathed gas. The wounded were brought below. We also learned of deaths. The Exodus was captured. The English tied our ship to their destroyer and towed us into the port of Haifa. After all the mayhem, the English had taken over the ship.

I stood next to a broken window and looked out over the beautiful landscape of Mt. Carmel that was lit up by lights that twinkled like stars in the night sky. I breathed in the warm air, the atmosphere of Eretz Israel, and so stood there for hours without feeling tired, until dawn broke. The port of Haifa came to life.

They took us off the ship and led us in a line to a building that stood on the pier. It was a long building, made of sheet metal. In the doorway stood a fat, crude-looking woman who held a can of Flit in her hand. She roughly lifted up my dress, which I was still wearing, and sprayed me with a strong dose of DDT. Then she sprayed my hair in the same way, from all sides. From the tin building we went directly to a British freighter, or what could more properly be called a jail, named Runnymede Park – a floating prison.

From this point on, we begin a new story: a journey into the unknown.

We descended to a large hall below deck. The ceiling was an iron grill, through which light and sometimes rays of sun penetrated. British soldiers patrolled around the grill-covered opening to ensure that we would not escape, as if there were some place we could escape to. If we were lucky, it would be to the depths of the sea. Each group grabbed a small area to itself for sleeping, body crammed up against body once again.

Our time was apportioned. I used it mainly to get rid of the stench from down below and to stay on deck to draw fresh air into my weak lungs. Sometimes we got food, which included stale biscuits with worms crawling in them and a gray liquid they called soup. We mostly gave the biscuits to our leader to keep for the smaller children who weren’t able to take part in the hunger strikes that were organized every few days by the higher echelons – people of the Hagana and the Mossad that I didn’t know.

Life on board the floating prison was unbearable: the perpetual hunger, dirt and awful crowding that caused disease, particularly among the children, who grew weaker from malnutrition. The hunger was tormenting and my belly rumbled endlessly. I sometime asked myself if I would ever have enough to eat, and what did bread taste like?

I remember the night that was perhaps the worst of all: on that night I awoke from hunger, raised myself up on my elbows and to my astonishment saw Tzvi, one of our leaders, a grown man with dark hair, sitting comfortably not far from where I lay and eating from our emergency box the little bit of food that was supposed to feed the smaller children. He gobbled up the little bit there was like a starving animal and at a certain moment, when he caught sight of me, his eyes flashed a warning. I understood that I was in trouble. I tried not to bump into him in the units. Fear of his revenge turned my life into a hell. Day followed day, and the hope that we would reach some shore diminished steadily.

On one of the days when we were allowed to go up on deck to breathe fresh air, a huge rock appeared on the horizon and as we approached we began to see a port where British ships were anchored. On their decks were Scottish soldiers wearing plaid kilts and red hats with red pompoms. We were in Gibraltar. In an impressive ceremony our jailers left us, to be replaced by Scottish soldiers. Something refreshing, perhaps a bit of hope, but “Where are we going now?”. Nobody could give us an answer. We left Gibraltar and returned to the awful routine. Once again, we lost hope.

It was still hot. The ship sailed on a smooth sea, but where to? Weeks passed and land was once again sighted on the horizon – France! Motorboats sped up to us, circling back and forth until one of them drew close up to us and a rope ladder was dropped down to it. Three people climbed up it, one of them a very pretty woman. For some reason, the British allowed her to come up to us children and, without saying a word, she gave out candies. We didn’t know how to thank her. Apparently our eyes said everything. I felt that she understood our situation.

The ships were anchored outside the port but the boats visited us every day for several weeks. There were people who got off the ship. Apparently they were no longer able to bear the awful suffering. I envied them. I had no choice. Of course, I too would have got off and possibly many others like me, but our reality was different.

One morning the ship sailed for the open sea, and once again I asked, “Where is it going? Where to, this time?” I soon found out – to Germany.

In the coming weeks the weather changed to rainy and cold and we weren’t prepared for such a drastic change. We had nothing to wear, nothing to cover ourselves with. Apparently we were approaching Germany quickly. It was autumn weather and maybe even winter had begun. Cold rain penetrated beneath the deck where we spent most of the day.

Nearly all of the children became sick. Every one of us wanted to be admitted for at least one day to the ship’s sick bay, where we would have a clean bed, a heated wardroom and even a bit of hot soup. The sick bay filled up quickly. The English admitted the patients, each in turn, for only a few hours. Later, all those seeking admittance were returned to the dirt from which they had come. For lack of choice we lay on the filthy floor, snuggling close together to preserve body warmth and to relieve the dizziness brought on by high fever.

Two weeks passed and one morning, our leader told us that we were nearing the port of Hamburg, on the coast of Germany, and that the English would disembark us, dead or alive. We gathered in small groups, and we were told to resist with all the strength we could still muster. They gave us yellow sheets of plastic, which apparently they had got in France for protection from the rain but now we were supposed to use them against the tear gas and water jets that the English were expected to use. We bunched together in corners, squeezed tightly together, and covered ourselves with the plastic as much as possible.

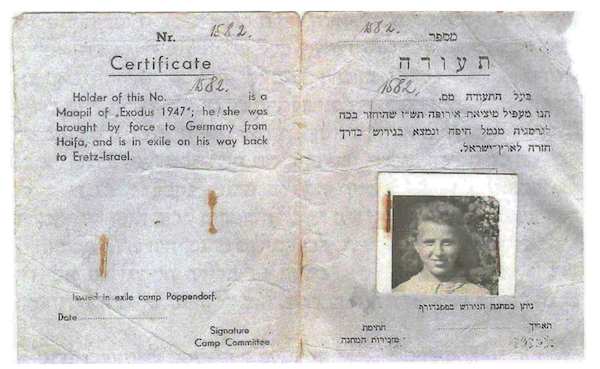

The English didn’t use tear gas, but they doused us with cold water jets as an introduction. After that, they grabbed every child by the feet, holding us head down like chickens about to be slaughtered, and dragged us to the deck and further on from there. I found myself on the train bound for Paffendorf, where there was a camp surrounded by an electrified barbed wire fence with a high sentry tower at each corner, from which the guards scanned the camp night and day with powerful searchlights. Within the camp there were rows of housing blocks with an especially long building at the center that held a row of showers and another row of water faucets, perhaps for washing hands. I entered the long building to wash my face and to relieve my great fatigue. I opened one of the faucets and my body shook out of control. A stream of water coursed over my body; my senses clouded. I thought my end had come. When I opened my eyes, I found that someone had turned off the water in time.

The kitchen was filled with German workers. I don’t know if we were intentionally given sweet pudding with potatoes in it. In any case, I ate, despite the disgust and the nausea I felt. Anything was better than the endless hunger.

Everyone got two army blankets. From one I made pants that one of the men sewed for me, apparently a tailor in his past life. Because of the many compliments I received, I also sewed for the smaller children. We suffered from cold. The clothing we had on wasn’t enough to warm our bodies, which had shrunk from lack of food. Winter had begun and the gates of the camp were closed and well guarded. Only ambulances bringing patients to the hospital in the city were allowed to leave. Every morning, I walked over to the gate in the hope that perhaps my father would come looking for us. Sometimes out of despair I thought that maybe my parents had forgotten that they had children? And if so, what happened to them? And what now? Where am I supposed to go? Day after day I made the same trip to the gate and was disturbed over and over by the same thoughts. One morning I came up to the gate and found it open. The guards had left. The camp was open. I waited for hours. No one left and no one entered. Why? I have no explanation. I could have left, but where to? The next day, I walked to the open gate again. In this way, the days passed.

One day, as I stood by the open gate as usual I noticed a man who was stooped over and dragging his feet with exhaustion. His hat had slipped down over his forehead. In my heart I prayed, “Maybe this is my father?” Maybe he’s looking for me, in spite of everything. My heart pounded. I cried out, “Papa!” He lifted his tired head and tears spilled from his eyes. From his lips came the whisper, “At last, I’ve found you! Where is your sister? And Dina?”

“We have all survived,” I answered in a whisper, “we’re all here, waiting for you.”

We left the camp and traveled a long way to reach the American sector. We reached München Neu Freimann. I began a new life.