The Return to Hebron

By Jerold S. Auerbach

In 1979—one week after Passover and 50 years after murderous Arab rioters destroyed the millennia-old Hebron Jewish community—a momentous decision was made. Jews living in the Kiryat Arba settlement, up the hill from Hebron, decided that it was time to return to their ancient sacred city, the burial site of the biblical patriarchs and matriarchs where King David ruled before relocating his throne to Jerusalem.

By community decision, women and children, who were least likely to provoke a harsh response from the Israeli government, would lead the way to Beit Hadassah, the former medical clinic in the heart of the decimated Jewish Quarter. At 4 a.m., 10 women with their 35 young children arrived by truck at the rear of the building. Assisted by teenage boys from Kiryat Arba, they climbed ladders, cut wires to enter through windows and unloaded necessary supplies: cooking burners, gas canisters, a refrigerator, water and a chemical toilet. It was not expected to be a brief visit.

The excited children began to sing v’shavu banim l’gvulam—God’s promise that the children of Israel would return to their ancient homeland. A puzzled Israeli soldier left his post on a nearby roof to investigate the noise. When he asked how they had entered the building, a 4-year old girl responded: “Jacob, our forefather, built us a ladder, and we climbed in.”

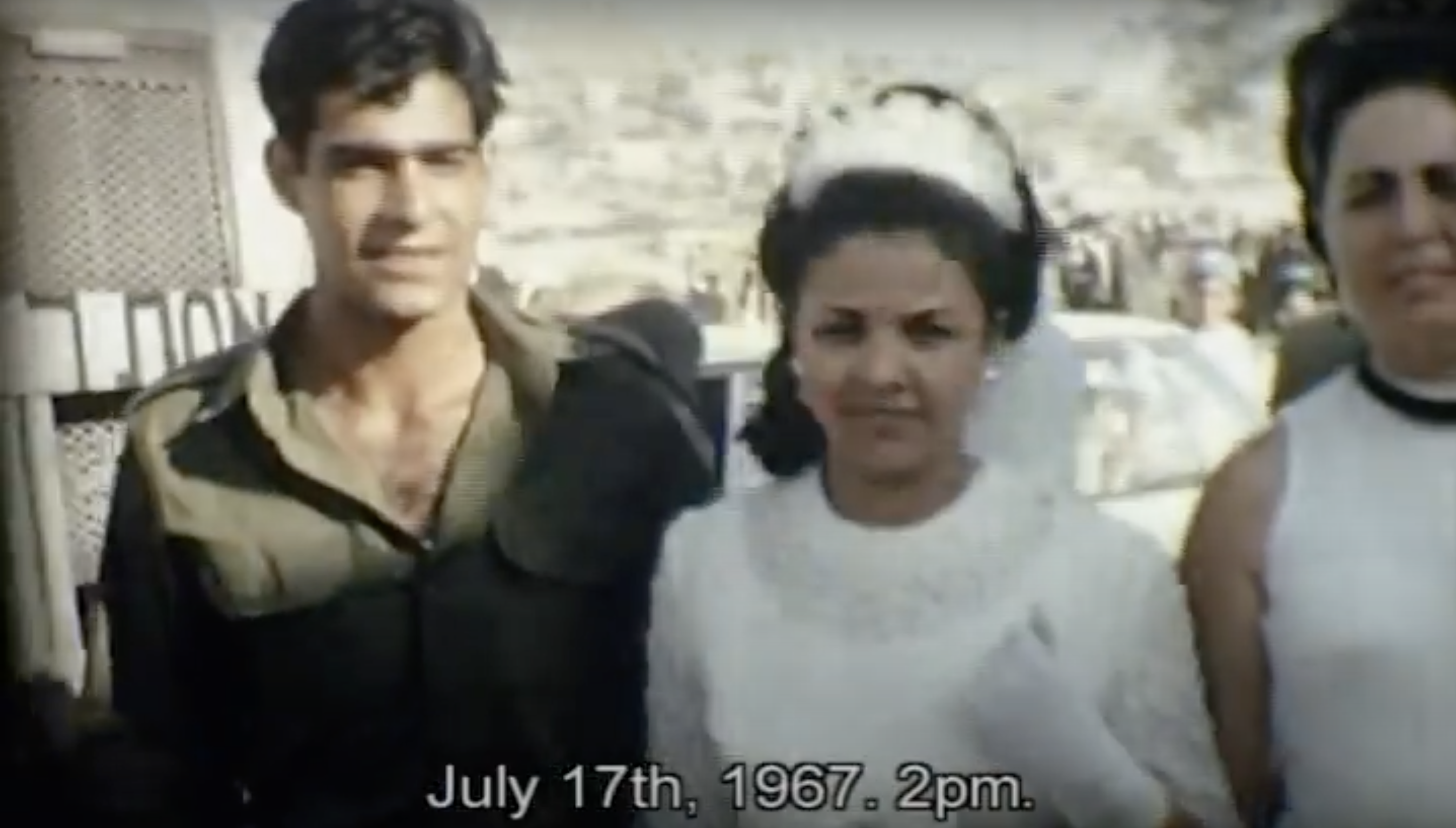

In their first message from Beit Hadassah, the women noted that they went to Kiryat Arba eight years earlier as a compromise with the government, although their strong preference was Jewish resettlement in Hebron. Miriam Levinger, the wife of Rabbi Moshe Levinger, who had led the return to Hebron for a Passover seder following the Six-Day War, declared that “Hebron will no longer be Judenrein.” As their first Shabbat in Beit Hadassah ended, yeshivah students came from Kiryat Arba to dance and sing outside. She insisted: “What was in the past in Hebron is what will happen in the future.”

Without electricity or running water, life was not easy. But the women were fiercely determined to remain, waiting for the government to authorize their presence. A pregnant woman refused to leave Beit Hadassah unless her return was assured. It was—and so she returned with her infant daughter, named Hadassah. The government finally agreed that every Friday evening at the beginning of Shabbat, one husband would be permitted to enter the building to recite Kiddush.

Despite their hardships, the women of Beit Hadassah had paved the way for the renewal of Jewish life in Hebron. “To be a Jew in Hebron,” recounted Miriam Grabovsky, “is to live as close as is possible to the Patriarchs and Matriarchs, and to absorb from them, every day, new strength.”

She added: “To be a mother in Hebron is to be a soldier without a uniform,” choosing “to actively participate in the process of redemption.”

With local Arabs infuriated by the presence of Jews, redemption proved costly. Violence mounted after the Israeli Cabinet narrowly voted to authorize the establishment of a yeshivah in Hebron. Following the conclusion of a Shabbat service in Machpelah, several dozen men and women walked together to Beit Hadassah for dinner. As they crossed the footbridge to enter, they were caught in a deadly crossfire of bullets and grenades from Arabs on a nearby rooftop. Six Israeli men were murdered. In time, a new building named Beit HaShisha (“House of the Six”) in their memory was constructed next to Beit Hadassah.

Despite repeated episodes of Arab violence, the tiny Jewish community endures. Although Hebron Jews were (and still are) lacerated by Israeli leftists as religious zealots, they remain determined to live where the deepest Jewish historical roots are implanted. In the first capital of ancient Israel, Judaism and Zionism converged when mothers with their young children courageously restored Jewish life in Hebron.

Originally published on JNS.org

Recommended for you:

About the Author