Four Portraits of People Who Experienced the Aliyah Bet

Meet 4 personalities whose experience during the Aliyah Bet helps us understand the significance of this underground immigration movement and its impact on Jewish lives as they fulfilled the dream of living free in our homeland.

MURRAY GREENFIELD

Murray Greenfield was born and grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in New York City, speaking English and Yiddish. He is a marvelous story-teller and superb salesman. But his modesty and humor hide a life-long devotion to the State of Israel in a myriad of ways, including the rescue by sea of Jews who survived the Holocaust, helping immigrants from North America as a founding member of AACI, and playing a leading role in the aliya of Ethiopian Jewry.

During World War II, Murray served in the Merchant Marines, and by late 1946, someone told him about “Aliyah Bet” – or “illegal immigration,” as the British termed the Jews who trying to enter Israel after surviving the Holocaust. He became one of 250 American volunteers who sailed on so-called “rust buckets” – vessels that were not made for long journeys – between 1946 and 1948, rescuing more than a third of Holocaust survivors from ports in Europe to Cyprus, Tel Aviv and Haifa.

Greenfield recounted his role, together with Joseph M. Hochstein, in his 1987 book, The Jews’ Secret Fleet, the untold story of North American participation in smashing the British blockade which led to the founding of the Jewish state. It later inspired a 2008 documentary film titled Waves of Freedom.

Greenfield says he was motivated by Ben-Gurion to write the book. The prime minister confessed to him that he knew nothing about the Jewish Americans who had rescued European Jews on ships after the Holocaust, and it should be documented for posterity.

“We created the Jewish state, with the help of these ships,” Greenfield says. “Of the 70,000-odd Jews who were brought to Palestine after World War II and before the state, over 50 percent came on American ships sailed by some 250 young men who were volunteers like myself.”

Greenfield believes that without the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine (which became UN General Assembly Resolution 181), the operation could never have been completed.

“We had to win the War of Independence, otherwise where would we be? But that was the next stage, because if the British had been told by the United Nations to keep Palestine, we couldn’t have won any war,” he says. “I’m sure when I look back at it all, the British did not believe the United Nations would vote in favor of two states. But once the British lost, because they’re law-abiding people, they gave up. And so I tell people that although I didn’t realize it at the time, we helped establish the Jewish state.” READ MORE »

RUTH KLUGER

In June 1939, there were nine members of the Mossad le Aliyah Bet. Ruth Klüger became the tenth, and the only woman. She was 25 years old. Her qualifications were well known to Berl Katznelson, a founder of the Histadrut, the labor union in Palestine where she worked. He knew she was born on April 24, 1914 in Kiev, was raised in Romania and that her mother was ”a dedicated Zionist.” He knew she graduated with a law degree from the University of Vienna, knew eight languages, and had been married to her husband, Emmanuel, for five years. He also knew a secret she thought no one knew – she had helped smuggle a group of Polish Jews out of Greece and into Palestine.

Returning to Palestine from a trip to Romania, Klüger had come across a group of 16 Jews at a port in Greece. Desiring to make it to Palestine, but having ”no certificates of entry, no legal papers, no money for tickets or bribes,” Klüger collected money from some Greek Orthodox priests as well as from some first-class passengers and then used the money to bribe two of the ship’s officers. The 16 Jews were dressed as sailors (the four girls in the group had to cut their hair) and escorted at night into an empty first-class cabin where they were locked up for the remainder of the trip.

One spontaneous illegal venture, however, could not have prepared Klüger for the rescue attempts she would help coordinate as a member of the Mossad. ”Our work is considered illegal by every government in the world,” she was told before joining. ”If you land in prison, we’ll have no way to get you out. You will disappear.” Acknowledging that her safety would be at risk and her personal life would cease, Klüger asked to join.

Under the pretense of selling shares of land in Palestine, Klüger left for Constantza, Romania and immediately set about the task of following up on leads regarding a 50-year-old ship, the Tiger Hill. Bargaining her way to a reasonable leasing fee she, in her naiveté, assigned herself the job of raising the initial portion of the funding to pay that fee. She accomplished this deed by employing some characteristic traits. Klüger was a fast-talker who used persuasive arguments and incited compassion in her audience. She committed facts and figures to memory and carried newspaper clippings and other written materials in her purse, ready to present them if and when she deemed necessary. No name or job title was to commandeering to intimidate Klüger. If she became aware of an individual who may be able to help the Mossad, she stopped at nothing to acquaint him or her with the necessity of getting Jews out of Europe and insisted that those who helped to make this possible would be considered saviors for making an effort. READ MORE »

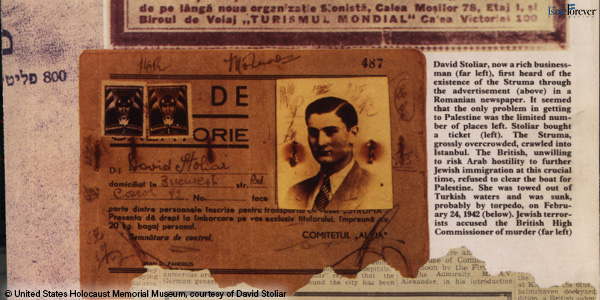

DAVID STOLIAR

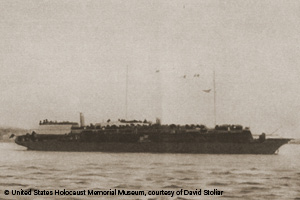

Stoliar signed up along with his fiancée, Ilse Lothringer, and her parents. But when they finally caught a first glimpse of the Struma in the Black Sea harbor of Constanta, it was a bad omen: The ship, originally meant for only 150 passengers, had been retrofitted to carry almost 800, in tiny wooden bunks on three low levels -- and that in the coldest winter in generations.

"Like sardines," Stoliar says. "We couldn't even turn over. But we had no way of going back." After several delays they finally put out to sea on December 12, 1941. Their route was supposed to take them through the Black Sea, the Bosporus and the Mediterranean to the port of Haifa. But they had gone only a few kilometers when the engine started sputtering - and then died completely as they approached the Bosporus.

A Turkish tugboat schlepped them to the harbor of Istanbul, supposedly to have the engine fixed. The refugees, lacking visas, were forbidden to disembark. Instead, the authorities raised the black and yellow quarantine flag over the Struma.

Meanwhile, a long, diplomatic tussle began behind the scenes. Great Britain refused to allow the Struma to continue on to Palestine. Romania didn't want it back, either. The United States stayed out of it completely. And Turkey, still neutral at the time and not wanting to get on the wrong side of anybody, forced the passengers to stay on board, where they were slowly starving. "We were not considered human,” Stoliar says.

Conditions on board worsened rapidly. Food became scarce; a pregnant woman suffered a miscarriage. The only help came from Simon Brod, a local Jewish businessman who rescued many refugees over the course of the war. He occasionally brought food and water. Turkey eventually took action on its own. On February 23, 1942, policemen stormed the Struma, cut the anchor chain, tugged the ship back into the Black Sea -- and set it helplessly adrift.

Indeed, that end came in the early hours of the following day -- in the form of a sudden explosion.

Most of the passengers were asleep, including Stoliar. "It was probably three or four in the morning," he says, now softly and haltingly. "I woke up as I was thrown into the air. I fell back into the water, and when I surfaced, there was no vessel anymore. Nothing. Just debris."

The story of the Struma faded into obscurity. Stoliar didn't mention the Struma again for several years. In 2003, Douglas Frantz and Catherine Collins, two former New York Times correspondents, reconstructed the tragedy in their book Death on the Black Sea. Stoliar, albeit reluctantly, was their main source.

So now he wants to stop talking about it altogether. "Why did the others die," he still asks himself, "but I didn't?" It's a question with no answer. READ MORE »

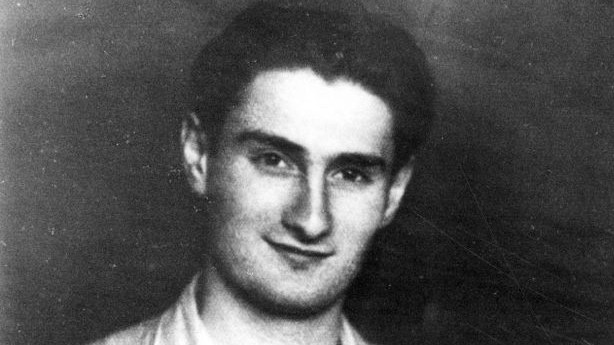

SHIMON KAUFMAN

World War II is over 1946 was a year to which we American Habonim had long looked forward. World War II had ended, and the dream of aliya was now an immediate objective. The years of preparation at Cream Ridge and the periods of military service were over. Military victory was ours, and Hitler had reached his ignominious end. Every one looked forward to a new and better world, and we were all certain that Britain would at last allow the broken remnant of European Jewry to return to its ancient homeland and that we American chalutzim would also soon be on our way to join them in building a new life in Palestine.

Jewish people are considered intruders

These fond hopes were not to be realized so quickly. The British Labor party, whose sympathy and promises had encouraged us in some of our darkest moments, had, upon coming to power, turned our fate over to the callous hands of Ernest Bevin. We soon learned that Mr. Bevin regarded the Jewish people as intruders on the Near Eastern landscape and that his best advice to the Jewish survivors of the death camps was to return to the cemeteries that their former homes had become. Nor did he hesitate to slam the doors in the faces of American chalutzim. The British would welcome no Jew to Palestine, be he a stateless displaced person, an American, or even a British citizen.

Aliya Bet It was during this period that we began to hear rumors about Aliya Bet, the so-called "illegal" immigration. Soon the press began to report regularly about the small, over laden ships that plied the Mediterranean and secretly attempted to land their human cargo at remote spots along the; Palestinian shore. It was not long before some of our comrades had the opportunity to participate in this activity. Two demobilized Canadian corvettes were acquired, and they sailed for Europe manned by Jewish volunteers. These two ships, the Hagana and the Wedgwood, -were to bring thousands of Jewish refugees from southern European poirts to Palestine, where they were finally captured by the British navy. 'The passengers and crews were interned at Atlit for a while before being given their freedom. The ships were left to rust at anchor off the Haifa breakwaters, but their story had a heroic sequel: they were to become the "capital ships" of the Israel navy during the War of Independence. READ MORE »